Film Friday: «Kitty Foyle» (1940)

In honor of Ginger Rogers' 105th birthday, which is tomorrow, this week on "Film Friday" I thought I would bring you one of my favorite films of hers. This is also the picture that gave her the only Academy Award for Best Actress of her career.

|

| Theatrical release poster |

Directed by Sam Wood, Kitty Foyle (1940) opens with Kitty Foyle (Ginger Rogers), a cosmetic saleswoman in a New York boutique owned by Delphine Detaille (Odette Myrtil), trying to decide whether she should marry Dr. Mark Eisen (James Craig) and be respectable or sail away with the already-married Wyn Strafford (Dennis Morgan), whom she has loved for many years and has just re-entered her life. As she wrestles with her conscience, Kitty thinks back to her youth in Philadelphia, where she lived with her Irish father, Tom (Ernest Cossart). Teenage Kitty is obsessed with the city's elite "Main Liners" and dreams of marrying a rich man, despite her father's warnings against getting carried away with her fantasies.

Five years later, Kitty meets the embodiment of her dreams in the wealthy Wyn Strafford, who is so charmed by the girl that he offers her a job as a stenographer at his fledging magazine. They soon fall in love, byt Wyn does not have the courage to break from his life in Philadelphia's Main Line by proposing to a woman so far below him socially. With the death of her father, Kitty goes to New York to work for Delphine. Although she still loves Wyn, she begins dating the charming doctor Mark. Wyn eventually finds Kitty in New York and the two marry shortly thereafter. However, when he takes her back home, his class-conscious family — especially his mother (Gladys Cooper) — insist that Kitty attend finishing school before she is introduced into proper Philadelphia society. Realizing the futility of the marriage, Kitty leaves the house in digust and they are divorced. She returns to New York, where she learns in rapid succession that she is pregnant and that Wyn is to marry a Philadelphia socialite (Kay Linaker). Kitty decides to have the baby on her own, but loses it in childbirth. Several years later, she returns to Philadelphia to open a branch store for Delphine. By chance, she waits on Wyn's wife and meets their young son. Finally, as Kitty ponders her past, she chooses respectability over love and marries Mark.

Kitty Foyle: Just a minute, Wyn. You needn't worry about me. I'm free, white and 21 — almost. And I'll go on loving you from here on out. Or until I stop loving you. But nobody owns a thing to Kitty Foyle — except Kitty Foyle.

Born in the Philadelphia suburb of Haverford, Christopher Morley published his first written work — a poetry collection entitled The Eighth Sin — while attending Oxford University in England in 1912. The following year, he went to work at Doubleday in New York as a reader and book publicist, before returning to Philadelphia in 1917 as an employee of the Ladies' Home Journal and then of the Evening Public Ledger. It was in Philadelphia that Morley released his first novel, Parnassus on Wheels, whose protagonist, travelling bookseller Roger Mifflin, appeared again in his second book, The Haunted Bookshop. In 1920, he moved back to New York, where he wrote a column for the Evening Post, helped establish the Baker Street Irregulars — the famed organization of Sherlock Holmes enthusiasts — and played key roles in the foundings of the Saturday Review of Literature and the Book of the Month Club. In the interim, Morley continued to write novels, short stories and poetry, in a body of work that often reflected his affection for Philadelphia.

In 1939, Morley published Kitty Foyle, the story of a working-class woman from Philadelphia who is conscious of social and class differences and their effect. When she falls in love with "Main Liner" Wyn, she refuses to marry him because she does not want to be "improved" by his family. Kitty discovers that she is pregnant and decides to have an abortion, before marrying a Jewish doctor at the end of the novel. Released by J. B. Lippincott & Co., Kitty Foyle was an instant success, especially amongst American women. In September of that year, RKO president George Schaefer began to consider the purchase of Morley's novel, as he was in need of vehicles for the studio's female performers. However, response to Kitty Foyle was largely negative within RKO's story department. One reader's report declared, "This is a slow, dull long-drawn-out account of a girl's life. [...] I am unable to see any screen value in this story." Schaefer ultimately ignored his readers' negative feeling towards Kitty Foyle and purchased the rights for $50,000 in late December 1939.

Five years later, Kitty meets the embodiment of her dreams in the wealthy Wyn Strafford, who is so charmed by the girl that he offers her a job as a stenographer at his fledging magazine. They soon fall in love, byt Wyn does not have the courage to break from his life in Philadelphia's Main Line by proposing to a woman so far below him socially. With the death of her father, Kitty goes to New York to work for Delphine. Although she still loves Wyn, she begins dating the charming doctor Mark. Wyn eventually finds Kitty in New York and the two marry shortly thereafter. However, when he takes her back home, his class-conscious family — especially his mother (Gladys Cooper) — insist that Kitty attend finishing school before she is introduced into proper Philadelphia society. Realizing the futility of the marriage, Kitty leaves the house in digust and they are divorced. She returns to New York, where she learns in rapid succession that she is pregnant and that Wyn is to marry a Philadelphia socialite (Kay Linaker). Kitty decides to have the baby on her own, but loses it in childbirth. Several years later, she returns to Philadelphia to open a branch store for Delphine. By chance, she waits on Wyn's wife and meets their young son. Finally, as Kitty ponders her past, she chooses respectability over love and marries Mark.

Kitty Foyle: Just a minute, Wyn. You needn't worry about me. I'm free, white and 21 — almost. And I'll go on loving you from here on out. Or until I stop loving you. But nobody owns a thing to Kitty Foyle — except Kitty Foyle.

Born in the Philadelphia suburb of Haverford, Christopher Morley published his first written work — a poetry collection entitled The Eighth Sin — while attending Oxford University in England in 1912. The following year, he went to work at Doubleday in New York as a reader and book publicist, before returning to Philadelphia in 1917 as an employee of the Ladies' Home Journal and then of the Evening Public Ledger. It was in Philadelphia that Morley released his first novel, Parnassus on Wheels, whose protagonist, travelling bookseller Roger Mifflin, appeared again in his second book, The Haunted Bookshop. In 1920, he moved back to New York, where he wrote a column for the Evening Post, helped establish the Baker Street Irregulars — the famed organization of Sherlock Holmes enthusiasts — and played key roles in the foundings of the Saturday Review of Literature and the Book of the Month Club. In the interim, Morley continued to write novels, short stories and poetry, in a body of work that often reflected his affection for Philadelphia.

In 1939, Morley published Kitty Foyle, the story of a working-class woman from Philadelphia who is conscious of social and class differences and their effect. When she falls in love with "Main Liner" Wyn, she refuses to marry him because she does not want to be "improved" by his family. Kitty discovers that she is pregnant and decides to have an abortion, before marrying a Jewish doctor at the end of the novel. Released by J. B. Lippincott & Co., Kitty Foyle was an instant success, especially amongst American women. In September of that year, RKO president George Schaefer began to consider the purchase of Morley's novel, as he was in need of vehicles for the studio's female performers. However, response to Kitty Foyle was largely negative within RKO's story department. One reader's report declared, "This is a slow, dull long-drawn-out account of a girl's life. [...] I am unable to see any screen value in this story." Schaefer ultimately ignored his readers' negative feeling towards Kitty Foyle and purchased the rights for $50,000 in late December 1939.

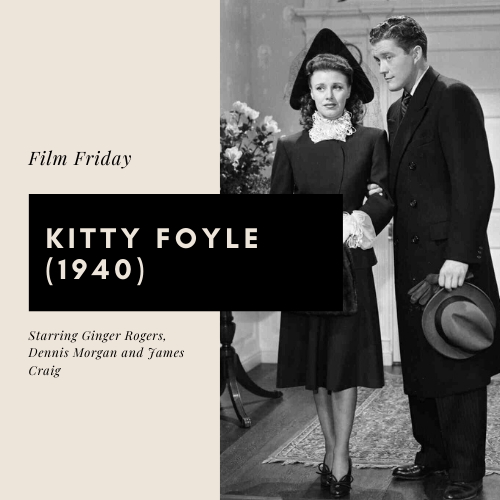

|

| Ginger Rogers and Dennis Morgan |

The script of Kitty Foyle was initially assigned to Donald Ogden Stewart, whose previous credits included Marie Antoinette (1938), Holiday (1938) and Love Affair (1939). When Stewart's screenplay was deemed "unshootable" by RKO, Schaefer recalled Dalton Trumbo from his three-month layoff to revise it. Trumbo, who would be blacklisted during Hollywood's anti-Communist purge in the late 1940s, agreed to take the assignment, but only on the condition that the studio cancel his contract after the script was finished.

Upon reading a synopsis of the novel, Joseph I. Breen, head of the Production Code Administration — and who would serve as general manager of RKO between 1941 and 1942 — informed the studio that "the material, in its present form, is definitely unacceptable, because it is a clear-cut violation of the Production Code." He cited three problems: "the suggestion of frequent illicit sex affairs between your two leads," Kitty's pregnancy and her subsequent abortion. Breen told RKO that these elements had to be removed from the script or the writer must "inject into the story the necessary compensating moral values of punishments."

To placate Breen, Trumbo devised a short-lived marriage between Kitty and Wyn and had their baby be stillborn instead of suggesting an abortion. Breen, however, was still not satisfied, describing the script as being "hardly more than a story of illicit sex without sufficient compensating moral values." Unless the "illicit sex relationship" was completely eliminated, the annulment scene clarified and the child shown to be the product of a post-annulment marriage, the script would not be approved. Although Trumbo's final screenplay maintained the couple's "illicit" night together, it met the rest of Breen's demands and he finally approved it for filming. According to a researcher for the American Film Institute, Trumbo retained much of Stewart's initial dialogue and another writer, Robert Ardrey — who would years later receive an Academy Award nomination for Khartoum (1966) — made a "significant" contribution to the continuity. Neverthless, Trumbo received sole credit for the screenplay of Kitty Foyle, while Stewart was given an "additional dialogue" mention. Morley's original flashback structure was retained in the film.

Upon reading a synopsis of the novel, Joseph I. Breen, head of the Production Code Administration — and who would serve as general manager of RKO between 1941 and 1942 — informed the studio that "the material, in its present form, is definitely unacceptable, because it is a clear-cut violation of the Production Code." He cited three problems: "the suggestion of frequent illicit sex affairs between your two leads," Kitty's pregnancy and her subsequent abortion. Breen told RKO that these elements had to be removed from the script or the writer must "inject into the story the necessary compensating moral values of punishments."

To placate Breen, Trumbo devised a short-lived marriage between Kitty and Wyn and had their baby be stillborn instead of suggesting an abortion. Breen, however, was still not satisfied, describing the script as being "hardly more than a story of illicit sex without sufficient compensating moral values." Unless the "illicit sex relationship" was completely eliminated, the annulment scene clarified and the child shown to be the product of a post-annulment marriage, the script would not be approved. Although Trumbo's final screenplay maintained the couple's "illicit" night together, it met the rest of Breen's demands and he finally approved it for filming. According to a researcher for the American Film Institute, Trumbo retained much of Stewart's initial dialogue and another writer, Robert Ardrey — who would years later receive an Academy Award nomination for Khartoum (1966) — made a "significant" contribution to the continuity. Neverthless, Trumbo received sole credit for the screenplay of Kitty Foyle, while Stewart was given an "additional dialogue" mention. Morley's original flashback structure was retained in the film.

|

| James Craig and Ginger Rogers |

The role of Wyn Strafford was reportedly sought by a number of actors, including George Brent, Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and David Niven, Rogers' leading men in In Person (1935), Having Wonderful Time (1938) and Bachelor Mother (1939), respectively. RKO eventually assigned the part to Dennis Morgan, working on loan-out from Warner Bros. A graduate of Carroll University, Morgan was an opera singer before MGM executives discovered him at the 1934 World's Fair in Chicago and brought him to Hollywood. He appeared in minor roles in several pictures under MGM and Paramount, but it was only when he began working at Warner Bros. in the late 1930s that he finally achieved widespread recognition. His previous credits included The Return of Doctor X (1939), with Humphrey Bogart; The Fighting 69th (1940), starring James Cagney and Pat O'Brien; and Three Cheers for the Irish (1940), with Priscilla Lane. Morgan and Rogers later reunited in Perfect Strangers (1950), a courtroom drama based on the play Ladies and Gentlemen by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur.

|

| Ginger Rogers and James Craig |

RKO shot Kitty Foyle at its studios during the summer of 1940. Upon the film's release in December 17, The New York Times commented, "Kitty

Foyle is a sentimentalist's delight. Ginger Rogers plays her with much

forthright and appealing integrity as one can possibly expect." For their part, Variety wrote, "Ginger

Rogers provides strong dramatic portrayal in the title role, aided by

competent performances by two suitors, Dennis Morgan and James Craig." Ginger Rogers won an Academy Award as Best Actress. Other contenders for Best Actress included Bette Davis in The Letter (1940), Martha Scott for Our Town (1940) and Katharine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story (1940). The film also received Academy Award nominations for Best Picture, Best Director and Best Screenplay. The movie earned profits of $1.5 million, becoming RKO's biggest hit of the year. The only other film of 1940 that scored more was The Road to Singapore (1940) with Bob Hope, Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour. Eight other films tied with Kitty Foyle as the second largest grossing movie of 1940: Arizona, Buck Benny Rides Again, The Fighting 69th, Northwest Mounted Police, Northwest Passage, Rebecca, Santa Fe Trail and Strange Cargo.

________________________

SOURCES:

Christopher Morley's Philadelphia edited and with an introduction by Ken Kalfus (1990) | Dalton Trumbo: Blacklisted Hollywood Radical by Larry Ceplair and Christopher Trumbo (2015) | Ginger Rogers: A Bio-Bibliography by Jocelyn Faris (1994) | RKO Radio Pictures: A Titan Is Born by Richard B. Jewell (2012) | TCMDb (Notes) |

Comments

Post a Comment