10 Hollywood Actors Who Served in World War I

In the early 20th century, the rise of Germany and the decline of the Ottoman Empire disturbed the long-standing balance of power in Europe, at the same time that unresolved territorial disputes and shifting alliances created rivalries and an arms race between the great powers. Growing tensions reached a breaking point on June 28, 1914, when the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne was assassinated by an young Bosnian Serb revolutionary, who intended to free Bosnia and Herzegovina from Austro-Hungarian rule. Austria-Hungary blamed Serbia, as the assassination team was helped by a Serbian secret nationalist group, and declared war in the following month. Russia immediately mobilised its troops in Serbia's defense, prompting Germany, who had an alliance with Austria-Hungary, to declare war on both Russia and its ally, France. The United Kingdom subsequently marched against Germany, leading to a widespread conflict.

Although the United States was a major supplier of war material to the Allies, it remained neutral in the first years of the war, in large part due to domestic opposition. However, due to Germany's unrestricted submarine warfare, most notably the sinking of the RMS Lusitania, which killed over a hundred American citizens, the U.S. declared war on the German Empire in April 1917. The United States entry into the war was a turning point in the conflict, as it provided the Allied Powers with a massive influx of resources and manpower, which ultimately created a decisive advantage against Germany. The war finally came to a close in November 1918, with the signing of armistices between the Allies and their defeated opponents.

As with any war, World War I prompted many men from all walks of life to join the armed forces and serve their countries in their hour of need. Some of these men actually became Hollywood movie stars after the war, establishing long-lasting careers and starring in some of the most iconic films in cinema history. Here are 10 male actors who served in World War I.

Humphrey Bogart (1899-1957) | U.S. Navy, 1918-1919

Bogart joined the U.S. Navy in May 1918. After four months of boot camp at the Pelham Bay Naval Training Station in New York, he was assigned as a helmsman to the transport ship SS Leviathan. Just as the crew was about to be shipped off to Europe, Germany surrendered and the war came to an end. However, Bogart still sailed with the Leviathan from Hoboken, New Jersey to Liverpool, England. In the six months that followed the armistice, the ship was tasked with ferrying American servicemen back to the United States from France and England. Reportedly, it was during this time that Bogart got the scar on his lip, which gave him his iconic lisp. He was discharged from the Navy in June 1919.

|

| (from left to right) Humphrey Bogart in his Navy uniform. He was a Seaman 2nd Class; the SS Leviathan in dazzle camouflage leaving Hoboken in 1918. |

Buster Keaton (1895-1966) | U.S. Army, 1918-1919

Keaton was drafted into the U.S. Army in July 1918. He was assigned to the 159th Infantry Regiment, 40th Infantry Division, and attended basic training for two weeks at Camp Kearny in San Diego County, California. In August, he sailed with the American Expeditionary Forces from Long Island, New York to Liverpool, England aboard the HMS Otranto. His unit was stationed in France, but never saw any action. Keaton mostly entertained the troops, drawing from his experience in vaudeville. During his time on the Western Front, surrounded by rain and mud, he suffered an ear infection that permanently impaired his hearing. He returned to the United States in February 1919 and was discharged as a Corporal two months later.

|

| (from left to right) Buster Keaton in his Army uniform; a scene from Doughboys (1930), which was inspired by Keaton's own experience in the war. |

Ronald Colman (1891-1958) | British Army, 1909-1915

Colman joined the London Scottish Regiment of the British Army in 1909 and was mobilised as a Private into the 1/14th Battalion when the war broke out in July 1914. In September, he and his battalion embarked at Southampton in the SS Winifred and arrived the next day at Le Havre, in the Normandy region of northern France. Six weeks later, they were sent to Ypres to reinforce the front. On October 31, 1914, during the Battle of Messines, fought in the Flanders region of Belgium, Colman was seriously wounded by shrapnel in his ankle after an exploding mortar shell threw him into the air. He was treated in the field ambulance and sent back to England the following day. After a six-day stay at St. Bartholomew's Hospital in London, he was transferred to the 3/14th Battalion and sent to Perth, Scotland, where he did light clerical duty. In May 1915, he was declared physically unfit for combat, leading to his discharge. His injuries left him with a permanent limp that he tried to hide for the rest of his career. For his services during the war, Colman was awarded the Victory Medal, the British War Medal, the 1914 Star with clasps and roses, and the Silver War Badge.

|

| (from left to right) Ronald Colman in the 1920s; a detachment of the London Scottish Regiment after defending the Messines Ridge, on October 31, 1914. |

Maurice Chevalier (1888-1972) | French Army, 1913-1916

Chevalier was drafted into the French Army in 1913 and was in the middle of his service when hostilities commenced. He was sent to the front line and was wounded by shrapnel in the back in the first weeks of combat. He was subsequently taken as a prisoner of war and incarcerated for two years at the Dörnitz Altengrabow POW camp in the Saxony region of Germany, where he learned English from a fellow prisoner. In 1916, he was released through the top-secret intervention of King Alfonso III of Spain, who used his diplomatic and military network abroad to intercede for thousands of prisoners on both sides. Decades later, Chevalier revealed,

«Through the King, it had been arranged that the French and Germans should exchange prisoners who were ambulance workers, so I became an ambulance worker. That is, I altered my identification papers, then claimed a mistake had been made in that I should have been sent back to France. Had the deception been discovered, my punishment would have been severe.»

After being freed, he returned to France and was declared unfit for any further military service, leading to his discharge. In 1917, he was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his bravery during the war.

|

| (from left to right) Maurice Chevalier in his Army uniform; group portrait of Australian POWs standing beside a grave at Altengrabow in 1918. |

Herbert Marshall (1890-1966) | British Army, 1916-1918

Marshall enlisted in the London Scottish Regiment of the British Army in June 1916 and was assigned to the 1/14th Battalion, the same as Ronald Colman. In January 1917, he was sent to France and on April 9, the first day of the Second Battle of Arras, he was shot in the right knee by a German sniper. He was taken to a medical unit at Abbeville, in northern France, and shipped back to England in May. After a series of operations, doctors were forced to amputate his leg below the hip and he remained hospitalised at St. Thomas' Hospital in London for 13 months. He was discharged from the British Army in May 1918 and fitted with a prosthetic leg, which caused him to walk with a slight limp for the rest of his life.

Of his time on the Western Front, Marshall recalled,

«I knew terrific boredom. There was no drama lying in the trenches 10 months. I must have felt fear, but I don't remember it. I was too numb to recall any enterprise on my part.»

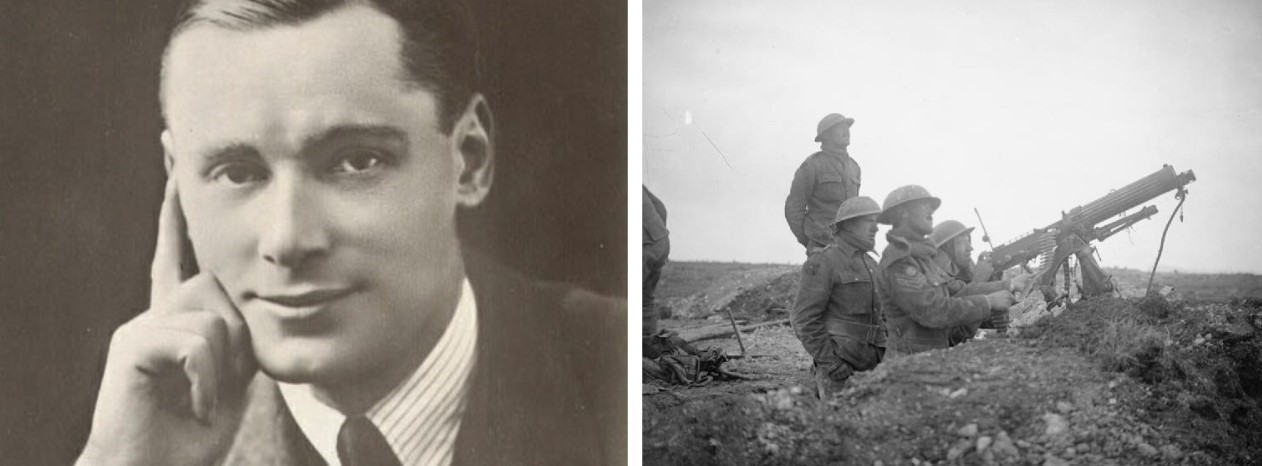

|

| (from left to right) Herbert Marshall c. 1920s; men of the British Machine Gun Corps firing on German aircraft during the Second Battle of Arras. |

Basil Rathbone (1892-1967) | British Army, 1915-1918

Rathbone joined the 1/14th Battalion of the London Scottish Regiment of the British Army in November 1915. After basic training, he was assigned as a lieutenant to the 2/10th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment, serving as an intelligence officer. In April 1917, he was posted to Bois-Grenier sector in northern France, where he got his first experience with warfare. In June 1918, after receiving news that his brother John had been killed in combat, Rathbone persuaded his commanding officer to allow him to scout for enemy positions near the town of Festubert. This reconnaissance mission was particularly dangerous because it would be carried out during daytime, and Rathbone and his platoon would be disguised as trees. They were spotted while crossing no man's land, but despite the heavy machine gun fire, Rathbone led his men to safety and the mission was a success. The daylight patrols continued into August and the information that was gathered was considered invaluable. For his «conspicuous daring and resource on patrol,» he was awarded the Military Cross. Rathbone was discharged in April 1919, having attained the rank of captain.

|

| (from left to right) Basil Rathbone in his uniform; members of the 2nd Australian Division (possibly the 17th Battalion) in the trenches in the Bois-Grenier sector. |

Claude Rains (1889-1967) | British Army, 1916-1919

Rains joined the London Scottish Regiment of the British Army in February 1916 and was also assigned to the 1/14th Battalion in France. In April 1917, during the Battle of Vimy Ridge, his unit was bombarded with heavy artillery and poison gas. Sustaining damages to his vocal chords and right eye, he was taken to the British Army's General Hospital 20 in Camiers, in northern France. His voice gradually returned, with the huskiness that would become his cinematic trademark, but he lost nearly all of the vision in his eye. He was shipped back to England to recuperate and, as he was still fit for service (although not for battle), he was commissioned as a Captain with the 13th Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment. He was discharged in February 1919. |

| (from left to right) Claude Rains in his Captain uniform; Canadian machine gunners during the Battle of Vimy Ridge, which was part of the Battle of Arras. |

Bela Lugosi (1882-1956) | Austro-Hungarian Army, 1914-1916

Lugosi joined the Austro-Hungarian Army shortly after the outbreak of war and was assigned to the Royal 43rd Infantry Regiment. He was sent to the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia (a region spanning what is now southeastern Poland and western Ukraine), where he served with a ski patrol and attained the rank of lieutenant. He was wounded twice: first in Rohatyn (now part of Ukraine), during a series of counterattacks against the Russian Empire; and later while on campaign in the Carpathian Mountains, in another surge against the advancing Russian troops. During the battle, exploding shells caused the trenches to collapse and Lugosi found himself trapped under a mound of corpses. In April 1916, he was discharged from the Army for «mental collapse.» He was awarded the Wound Medal for injuries sustained while serving on the Russian Front. |

| (from left to right) Bela Lugosi in his uniform; Austro-Hungarian troops advancing in the Carpathian Mountains (c. 1914 or 1915). |

Conrad Veidt (1893-1943) | Imperial German Army, 1914-1917

Veidt enlisted in the Imperial German Army in December 1914 and was assigned to the Eastern Front, near Warsaw, Poland. In August 1915, he took part in the Battle of Warsaw, a German offensive against the Russian Empire. Also known as the Great Retreat, the offensive was a humiliating defeat for the Imperial Russian Army, who began a withdrawal into the Baltics. Afterwards, Veidt contracted jaundice and pneumonia, and had to be evacuated to a military hospital in East Prussia. Instead of sending him back to combat, the Germans gave him the mission of using his acting skills on the front lines to keep the soldiers' morale high. He was re-examined in late 1916 and declared medically unfit for further active duty. He was given a full discharge in January 1917.Raymond Massey (1896-1983) | Canadian Army, 1914-1919

Massey enlisted in the Canadian Army when the war broke out. Commissioned as a lieutenant, he was sent to the Western Front as part of the 4th Brigade Canadian Field Artillery. In June 1916, he was wounded and shell-shocked in the Battle of Mont Sorrel, near Ypres, in Belgium. He returned to Canada for recovery and was assigned as an Army instructor for American officers at Yale University. In September 1918, he was called back to active duty and joined the 85th Battery Canadian Field Artillery, an unit of the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force that participated in the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. He was discharged in 1919. |

| (from left to right) Raymond Massey in his Army uniform; Canadian troops advancing under smoke during the Battle of Mont Sorrel. |

Several other Hollywood legends served during World War I on both sides of the conflict. These include: Adolphe Menjou (United States Army Ambulance Service); Walter Brennan (101st Field Artillery Regiment, United States Army); William A. Wellman (Lafayette Flying Corps, French Air Force); Fritz Lang (Austro-Hungarian Army); Michael Curtiz (Austro-Hungarian Army); Leslie Howard (3/1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry Regiment, British Army); Cedric Hardwicke (London Scottish Regiment, British Army); and Randolph Scott (2nd Trench Mortar Battalion, 19th Field Artillery Regiment, United States Army).

__________________________________________

SOURCES:

Claude Rains: A Comprehensive Illustrated Reference by John T. Soister (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2015)

Conrad Veidt on Screen: A Comprehensive Illustrated Filmography by John T. Soister (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2015)

The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosi by Arthur Lenning (The University Press of Kentucky, 2013)

The Secret Life of Humphrey Bogart: The Early Years (1899-1931) by Darwin Porter (The Georgia Literary Association, 2003)

«Buster Keaton: Comedian, Soldier» by Master Sergeant Jim Ober (California State Military Museum)

«Conrad Veidt» in The German Way & More

«Dracula Goes to War» by William Poole (Military History Now, October 29, 2019)

«Lieutenant Raymond Hart Massey» (Canadian Great War Project)

«Major Raymond H. Massey» (Vancouver Gunners)

«My Career at the Rear: Buster Keaton in World War I» by Martha R. Jett (worldwar1.com)

«Roll of honour: 15 movie legends who served in the First World War» by David Parkinson (BFI, November 7, 2018)

«The Hollywood Battalion» by James Cronan (The National Archives, October 7, 2014)

«The Hollywood Battalion - part 2» by James Cronan (The National Archives, October 20, 2014)

What a cool post! The only one I really knew about was Herbert Marshall. I didn’t know about how Bogie got his lisp! Also, baby Claude Rains lol

ReplyDeleteThanks, Phyl.

DeleteI knew about Herbert Marshall, Bogie, Ronald Colman, Basil Rathbone, Claude Rains and Buster Keaton. The others I had no idea.

I kind of wonder if Bogart's lip got in the way of someone's fist. Seems like the sort of thing that would happen on a ship full of soldiers.

ReplyDeleteFrom what I've read, that's one of the possibilities of how it might have happened, yes. However, there are a lot of conflicting stories about what really happened, so I guess we'll never know for sure how he got the scar on his lip.

Delete