The Classic Movie History Project Blogathon: Juvenile Delinquency in Mid-1950s Cinema

During the eight-year presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower, at the height of the Cold War, the United States was the most influential economic power in the world. Despite constant threats of Communism and nuclear annihilation, it looked as though the «American Dream» was finally a reality. People across the country were comfortably complacent, indulging in new cars, suburban houses, television sets and all sorts of new consumer goods. For the nation's adults, who still remembered the hardships of the Great Depression, life had never been better. However, for their teenage children, who had grown up during World War II, shielded from the most worrying of its effects, life was flawed by powerful feelings of alienation and anger.

As the number of teens doubled in the wake of the post-war baby boom, young people began turning their backs on the conformist ideals promoted by adult society. Parents could no longer impress their value system on their children, who longed for greater excitement and freedom, and felt the need to establish their own culture separate from adults. Economically independent due to the prosperity of the era, teenagers indulged in sleek and sporty cars, cruised the highways and frequented fast-food restaurants and drive-in movies — all while embracing the reckless, thrilling beat of rock 'n' roll music as the soundtrack of their generation.

There have always been inner-family conflicts between parents and their adolescent children, but they took on unprecedented proportions in the 1950s. Parents of the era were appalled by the lifestyle of their kids, who preferred to «shake, rattle and roll» to the sounds of Little Richard and Fats Domino instead of spending a quiet evening with their families.

Determined to contain what they considered to be reckless behaviour, parents imposed a new set of rules and restrictions upon their teenage children, which only caused further strain between the generations and led kids to rebel against their elders. At the time, all rebellious teen behaviour was seen as evidence of a growing problem with juvenile delinquency. It did not really matter whether teens were breaking laws or simply bending household rules; every aspect of the emerging youth culture was seen as both threatening and incomprehensible.

Meanwhile, the American film industry was facing a crisis of its own. In 1946, 100 million people went to the cinema each week, but by 1950 weekly attendance at movie houses had dropped to 40 million. Mass movements to the suburbs, marriages, babies, and the advent of television had distracted many people from cinema-going, and even he exotic lures of Technicolor, CinemaScope and 3D did not seem to be enough to drive audiences to the movies. Teenagers in particular were tired of the conventional portrayals of men and women, and the nostalgic films preferred by the older generation. They did not want the Clark Gables and the Cary Grants; they wanted new symbols of rebellion, someone who thought and felt exactly like them. In the mid-1950s, the gradual relaxation of the Hays Production Code and the growth of independent cinema allowed American filmmakers to openly explore taboo-breaking subjects around sexuality, crime, the use of drugs, and the theme of the day, juvenile delinquency. In early 1953, producer Stanley Kramer approached Marlon Brando with an idea for a film based on Frank Rooney's short story The Cyclist's Raid. It was inspired by real-life events that happened on July 4, 1947, when a gang of rough motorcyclists terrorized the citizens of a small town in Northern California. Its focus would be on «youthful rebels in search of excitement, anything to contain their huge unchanneled energy.» Its name, The Wild One (1953).

Between 1954 and 1956, juvenile delinquency was the hot topic of the day everywhere across America. Radio and television specials, books, newsreels, magazine articles, newspaper editorials and civic and church groups lamented the anti-social tendencies of the nation's teenagers. Many blamed the mass media and the alienated young heroes that populated teen-oriented television programs, comic books and films for initiating this «temporary American social disease.» This fear, however, did not represent actual increases in juvenile crime so much as the transformations of the post-war era. What perhaps the adult society of the time failed to realize was that times were changing, and kids were changing right along with them. Within a few years, those same teenagers that were once called delinquents had grown up to become the most idealistic generation in American history, a group committed to civil rights and peace.

As the number of teens doubled in the wake of the post-war baby boom, young people began turning their backs on the conformist ideals promoted by adult society. Parents could no longer impress their value system on their children, who longed for greater excitement and freedom, and felt the need to establish their own culture separate from adults. Economically independent due to the prosperity of the era, teenagers indulged in sleek and sporty cars, cruised the highways and frequented fast-food restaurants and drive-in movies — all while embracing the reckless, thrilling beat of rock 'n' roll music as the soundtrack of their generation.

|

| LEFT: Exterior of a McDonald's drive-in fast food restaurant in Chicago, Illinois (c. 1956). RIGHT: A group of teenagers having fun in a convertible car. |

Determined to contain what they considered to be reckless behaviour, parents imposed a new set of rules and restrictions upon their teenage children, which only caused further strain between the generations and led kids to rebel against their elders. At the time, all rebellious teen behaviour was seen as evidence of a growing problem with juvenile delinquency. It did not really matter whether teens were breaking laws or simply bending household rules; every aspect of the emerging youth culture was seen as both threatening and incomprehensible.

|

| LEFT: A family sitting in their living room watching television (c. 1955). RIGHT: A group of teenagers dancing in Palm Beach, Florida. |

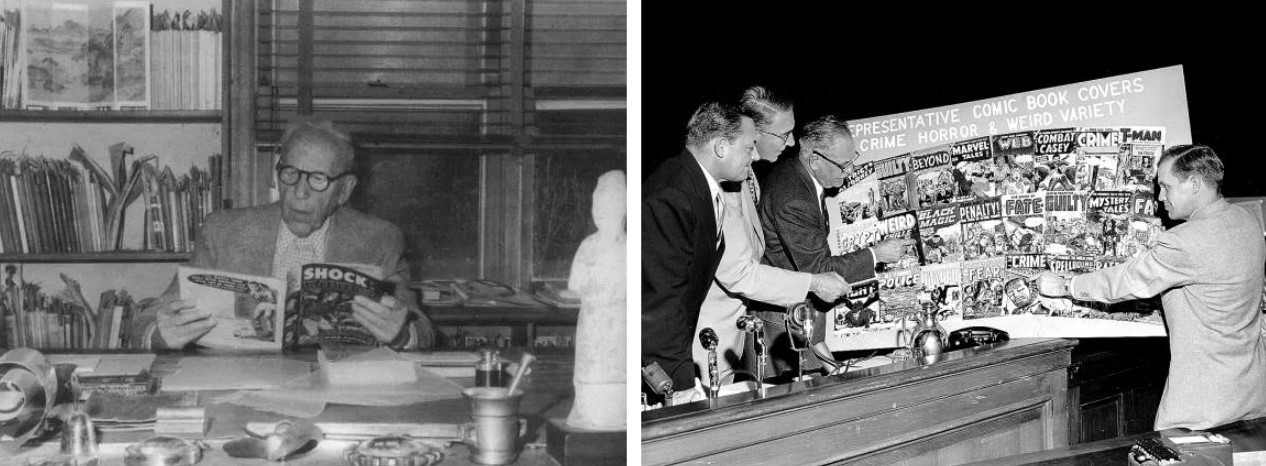

During the 1950s, the problem of juvenile delinquency became a near obsession not only with parents, but also with teachers, psychologists and law enforcement officials. In 1953, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover reported that in the United States young people under the age of 18 were responsible for 54% of all car thefts, 49% of all burglaries, 18% of all robberies and 16% of all rapes. A series of explanations were quickly offered to justify the phenomenon of juvenile crime, including rock 'n' roll music, television, divorce, the rise of a consumer culture, and even Communism. But perhaps the most (in)famous explanation was the one given by psychologist Fredric Wertham in his book Seduction of the Innocent (1954), in which he judged comic books, especially horror and crime comics, to be the root of all delinquent behaviour in adolescents.

In the course of his work with teen offenders, Wertham noted how avidly they read comic books and how excitedly they described their sometimes gruesome and morbid content. Because the young criminals studied by Wertham had all read comic books, he concluded that comics exerted unhealthy influence, ultimately cultivating juvenile delinquency. Although Wertham's study was highly flawed, particularly because he did not measure the delinquents against a control group of non-delinquents, his book was taken seriously and created great alarm in parents, who started campaigning for censorship. During hearings before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency in 1954, led by anti-crime crusader Estes Kevaufer, Wertham testified, «I think Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic book industry.»

In the course of his work with teen offenders, Wertham noted how avidly they read comic books and how excitedly they described their sometimes gruesome and morbid content. Because the young criminals studied by Wertham had all read comic books, he concluded that comics exerted unhealthy influence, ultimately cultivating juvenile delinquency. Although Wertham's study was highly flawed, particularly because he did not measure the delinquents against a control group of non-delinquents, his book was taken seriously and created great alarm in parents, who started campaigning for censorship. During hearings before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency in 1954, led by anti-crime crusader Estes Kevaufer, Wertham testified, «I think Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic book industry.»

Meanwhile, the American film industry was facing a crisis of its own. In 1946, 100 million people went to the cinema each week, but by 1950 weekly attendance at movie houses had dropped to 40 million. Mass movements to the suburbs, marriages, babies, and the advent of television had distracted many people from cinema-going, and even he exotic lures of Technicolor, CinemaScope and 3D did not seem to be enough to drive audiences to the movies. Teenagers in particular were tired of the conventional portrayals of men and women, and the nostalgic films preferred by the older generation. They did not want the Clark Gables and the Cary Grants; they wanted new symbols of rebellion, someone who thought and felt exactly like them.

Although Brando was intrigued by the concept of alienated youth, he was not impressed by the film's final script, after it had been severely altered by the Breen Office, Hollywood's self-imposed censorship board. He only accepted the lead role out of respect for Kramer, who had produced his critically acclaimed film debut, The Men (1950). Brando tried his own hand at rewrites, but it did no good, so he ended up simply ad-libbing and improvising entire scenes, which resulted in the inarticulate eloquence he would become known for.

Directed by László Benedek, The Wild One starred Brando as Johnny Strabler, the charismatic leather-clad leader of the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club. After being thrown out of a racing event for causing trouble, the Black Rebels ride into the town of Wrightsville, where they continue their general disturbance tactics before things escalate with the arrival of a rival biker gang. Along the way, Johnny falls for the sheriff's daughter, gets savagely beaten up by vigilantes after being mistaken for a rapist, and is arrested for a crime he did not commit.

Directed by László Benedek, The Wild One starred Brando as Johnny Strabler, the charismatic leather-clad leader of the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club. After being thrown out of a racing event for causing trouble, the Black Rebels ride into the town of Wrightsville, where they continue their general disturbance tactics before things escalate with the arrival of a rival biker gang. Along the way, Johnny falls for the sheriff's daughter, gets savagely beaten up by vigilantes after being mistaken for a rapist, and is arrested for a crime he did not commit.

While The Wild One is highly regarded today, it was a failure upon its initial release, with critics finding it exploitative and overly violent. The film particularly horrified parents, who feared that it might set a bad example for their teenage children and lead to an imitation of crime. Kids, on the other hand, were fascinated by it and soon began emulating Brando's distinctive style. White T-shirts, leather jackets and blue jeans — a wardrobe personally selected by Brando, which he wore to and from the Columbia studio lot every day — became symbols of youth rebellion and turned the 29-year-old actor into an icon for the age. The famous exchange between Johnny and a waitress (played by Peggy Maley) was the perfect expression of youthful alienation from core American values of the time and became another 1950s emblem. When the girl asks him, «What are you rebelling against, Johnny?» he responds, «Whaddya got?»

In A Cycle of Outrage: America's Reaction to the Juvenile Delinquent in the 1950s, James Gilbert wrote,

«Brando's character is riven with ambiguity and potential violence — a prominent characteristic of later juvenile delinquency heroes. One the other hand, he is clearly not an adolescent, but not yet and adult either, belonging to a suspended age that seems alienated from any recognizable stage of development. [...] In the end he rides off alone [...] he cannot find whatever it is he is compelled to seek.»

|

| Marlon Brando in publicity stills for The Wild One. |

Following the success of The Wild One among teenage moviegoers, Hollywood realized the potential of the affluent adolescent population and began meeting their demands for products that reflected their sensibilities. In 1954, MGM entrusted writer and director Richard Brooks, known for his affinity for sensationalist material, with the task of adapting Evan Hunter's most recent best-selling novel, The Blackboard Jungle, into a film. Since the book dealt with unruly students in an urban high school, the studio reasoned that a film version would not only attract a big youth market, but also tap into adults' anxiety about juvenile delinquency.

Blackboard Jungle (1955) featured Glenn Ford as Richard Dadier, a war veteran and recently certified English teacher assigned to an all-male inner-city school in New York, where the students make the rules and the staff meekly follows along out of fear and apathy. The working-class and racially diverse pupils, led by the bright but alienated African-American student Gregory Miller (Sidney Poitier), constantly defy their idealistic teacher, who makes various unsuccessful attempts to engage their interest in education. As Dadier tries to cope with class rowdiness and tensions between school and home life, he is subjected to violence as well as duplicitous schemes, most of which are perpetrated by the anti-Establishment youth Artie West (Vic Morrow). But he forges on; «I've been beaten up, but I'm not beaten,» he says. He eventually manages to gain the respect of some his students, particularly Miller, who ends up protecting him against a knife-wielding West in the film's climatic scene.

Blackboard Jungle (1955) featured Glenn Ford as Richard Dadier, a war veteran and recently certified English teacher assigned to an all-male inner-city school in New York, where the students make the rules and the staff meekly follows along out of fear and apathy. The working-class and racially diverse pupils, led by the bright but alienated African-American student Gregory Miller (Sidney Poitier), constantly defy their idealistic teacher, who makes various unsuccessful attempts to engage their interest in education. As Dadier tries to cope with class rowdiness and tensions between school and home life, he is subjected to violence as well as duplicitous schemes, most of which are perpetrated by the anti-Establishment youth Artie West (Vic Morrow). But he forges on; «I've been beaten up, but I'm not beaten,» he says. He eventually manages to gain the respect of some his students, particularly Miller, who ends up protecting him against a knife-wielding West in the film's climatic scene.

Advertised as «the most startling picture in years,» Blackboard Jungle targeted parents and educators, but the film's natural audience was teenagers, who flocked to the theaters to see it, drawn to the hip styles, slang and music. This was the first time a film featured a rock 'n' roll soundtrack, with the song «Rock Around the Clock» by Bill Haley & His Comets accompanying the opening and closing sequences. Chosen by Richard Brooks from the record collection of Glenn Ford's nine-year-old son, Peter, the song became an instant hit, with teens enthusiastically dancing to it in the aisles in theaters where the film played.

Besides being terrified by the film's use of rock 'n' roll music, parents strongly disapproved of its multi-racial cast. Teenagers, however, had found yet another icon of rebellion. Like Brando, Sidney Poitier was past his teens, but his screen persona embodied «a generation of Americans less bound by behavioral, sexual, or racial convention» and resembled «the emergent hero of 1950s American youth culture: silky, sullen, sexually charged.»

Gregory Miller's race and cool style might have exemplified the threat of juvenile delinquency, but his actions ultimately defused it. The film's closing scene shows Miller and Dadier shaking hands in mutual respect, with the former choosing education over crime, presumably embarking down a respectable path towards middle-class stability. Even with this cinematic attempt to suggest that reconciliation between parents and their adolescent children was still a possibility, Blackboard Jungle exposed the nation's anxiety over youth culture, convincing many Americans that teenagers were «smouldering with rebellion.»

Gregory Miller's race and cool style might have exemplified the threat of juvenile delinquency, but his actions ultimately defused it. The film's closing scene shows Miller and Dadier shaking hands in mutual respect, with the former choosing education over crime, presumably embarking down a respectable path towards middle-class stability. Even with this cinematic attempt to suggest that reconciliation between parents and their adolescent children was still a possibility, Blackboard Jungle exposed the nation's anxiety over youth culture, convincing many Americans that teenagers were «smouldering with rebellion.»

As the paranoia over wayward teenagers intensified, Senator Kefauver continued his crusade against juvenile crime, denouncing it as «a symptom of the weakness in our whole moral and social fabric.» In July 1955, four months after the release of Blackboard Jungle, the Kefauver Committee arrived in Hollywood to further investigate the impact of the mass media on juvenile delinquency, with Brooks' film assuming a central role in the proceedings. In the end, the senators never established a direct link between popular culture and youth violence, and the controversy around the hearings only increased the film's success among teenage audiences.

While Brooks was working on Blackboard Jungle, director Nicholas Ray began developing his own juvenile delinquency picture. When Ray approached Warner Bros. in September 1954 and proposed a film about «kids, young people growing up, their problems,» the studio suggested he adapt Robert Lindner's 1944 best-selling book Rebel Without a Cause: The Hypnoanalysis of a Criminal Psychopath, which they had owned the film rights to since 1946. The book was a case study of a disturbed youth from a poor background, whom Lindner, a psychologist specialized in the study and treatment of juvenile delinquency, had counseled at a federal prison. Ray, however, had no interest in the story; he thought the main character was too «abnormal» and he wanted to make a film about «normal» delinquents, «the kind who lived next door.»

Ray had already made two films about young people from poor backgrounds, the noirs They Live By Night (1948) and Knock on Any Door (1949), and he had no desire to make another one. Unlike perhaps everyone else in America, he understood that there was a sense of restlessness and alienation among the nation's teens that had nothing to do with poverty or the criminal underclass. Therefore, he wanted to avoid what he called «slum area rationalizations» and make a film that focused on middle-class teenagers, going beyond the notions of juvenile delinquency of the time and giving them a greater emotional depth. In a matter of days, Ray himself wrote a 17-page treatment that became the quintessential teen picture of the 1950s.

Ray had already made two films about young people from poor backgrounds, the noirs They Live By Night (1948) and Knock on Any Door (1949), and he had no desire to make another one. Unlike perhaps everyone else in America, he understood that there was a sense of restlessness and alienation among the nation's teens that had nothing to do with poverty or the criminal underclass. Therefore, he wanted to avoid what he called «slum area rationalizations» and make a film that focused on middle-class teenagers, going beyond the notions of juvenile delinquency of the time and giving them a greater emotional depth. In a matter of days, Ray himself wrote a 17-page treatment that became the quintessential teen picture of the 1950s.

Written by Stewart Stern based on Ray's storyline, Rebel Without a Cause (1955) told the story of Jim Stark (James Dean), a troubled teenager struggling to make sense of his middle-class upbringing and the gnawing restlessness within himself, made worse by his parents' indifference towards his problems and concerns. Jim feels betrayed and anguished by his constantly bickering parents (Jim Backus and Ann Doran), but even more so by his father's submissive attitude and failure to stand up to his wife and mother-in-law, who lives with them.

On the first day at his new school, fellow students treat Jim as a complete outsider, particularly the gang of delinquents led by Buzz Gunderson (Corey Allen), who soon challenges him for an ill-fated «chickie run.» Luckily, Jim eventually finds kindred spirits in Judy (Natalie Wood) and Plato (Sal Mineo), two other middle-class teenagers struggling with their own family problems and frustrations. The three soon form an unconventional and understanding «family» of their own, which brings them love, acceptance and security, before it all comes crashing down in a climatic scene that almost resembles the last act of a Greek tragedy.

On the first day at his new school, fellow students treat Jim as a complete outsider, particularly the gang of delinquents led by Buzz Gunderson (Corey Allen), who soon challenges him for an ill-fated «chickie run.» Luckily, Jim eventually finds kindred spirits in Judy (Natalie Wood) and Plato (Sal Mineo), two other middle-class teenagers struggling with their own family problems and frustrations. The three soon form an unconventional and understanding «family» of their own, which brings them love, acceptance and security, before it all comes crashing down in a climatic scene that almost resembles the last act of a Greek tragedy.

While all earlier juvenile delinquency pictures were set amid urban decay, Rebel Without a Cause took place in an affluent suburb, therefore destroying the nation's «common knowledge» that juvenile delinquents came from homes characterized by poverty and deprivation. Moreover, the film made it clear that it was actually the failure of middle-class families, the so-called «good families,» that was to blame for the main characters' troubles and frustrations. Juvenile crime was no longer a problem of the lower classes; it was lurking in the supposedly perfect suburbs and the delinquent was «the well-dressed boy or girl next door who was about to explode.»

Released a month after James Dean's tragic and widely publicized death, Rebel Without a Cause outraged concerned parents, but it soon grew into one of the most successful and influential pictures of the 1950s. Dressed in his blue jeans, white T-shirt and red leather jacket, Dean provided young people with a new icon of teenage anomie and alienation, becoming the ultimate alter-ego for their own growing restlessness with the conformity of the Eisenhower era.

Released a month after James Dean's tragic and widely publicized death, Rebel Without a Cause outraged concerned parents, but it soon grew into one of the most successful and influential pictures of the 1950s. Dressed in his blue jeans, white T-shirt and red leather jacket, Dean provided young people with a new icon of teenage anomie and alienation, becoming the ultimate alter-ego for their own growing restlessness with the conformity of the Eisenhower era.

Although Blackboard Jungle started a wave of youth-oriented pictures, it still viewed teenagers through the eyes of an adult authority figure, and the motivation behind the students' actions was left unexplored. It was only until Rebel Without a Cause that films finally allowed the post-war American teenager their own voice about their life and their feelings of alienation. When in the film Jim cries, «You're tearing me apart!» he is speaking for an entire generation of youngsters alienated from the restrictions and contradictions of the adult world around them.

François Truffaut commented on the influence James Dean had on teenage audiences:

«In James Dean, today's youth discovers itself. Less for the reasons usually advanced: violence, sadism, hysteria, pessimism, cruelty and filth, than for others infinitely more simple and commonplace: modesty of feeling, continual fantasy life, moral purity without relation to everyday morality but all the more rigorous, eternal adolescent love of tests and trials, intoxication, pride, and regret at feeling oneself «outside» society, refusal and desire to become integrated and, finally, acceptance — or refusal — of the world as it is.»

|

| James Dean as Jim Stark in Rebel Without a Cause. |

Between 1954 and 1956, juvenile delinquency was the hot topic of the day everywhere across America. Radio and television specials, books, newsreels, magazine articles, newspaper editorials and civic and church groups lamented the anti-social tendencies of the nation's teenagers. Many blamed the mass media and the alienated young heroes that populated teen-oriented television programs, comic books and films for initiating this «temporary American social disease.» This fear, however, did not represent actual increases in juvenile crime so much as the transformations of the post-war era. What perhaps the adult society of the time failed to realize was that times were changing, and kids were changing right along with them. Within a few years, those same teenagers that were once called delinquents had grown up to become the most idealistic generation in American history, a group committed to civil rights and peace.

This post is my contribution to The Classic Movie History Project Blogathon co-hosted by Movies Silently, Once Upon a Screen and Silver Screenings, and sponsored by Flicker Alley. To view all entries to the blogathon, click the links below.

________________________________________________

SOURCES:

A Cycle of Outrage: America's Reaction to the Juvenile Delinquent in the 1950s by James Gilbert (Oxford University Press, 1986)

American Culture in the 1950s by Martin Halliwell (Edinburgh University Press, 2007)

American Education in Popular Media: From the Blackboard to the Silver Screen edited by S. G. Terzian and P. A. Ryan (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015)

Batman and Psychology: A Dark and Stormy Knight by Travis Langley (John Wiley & Sons, 2012)

Historical Dictionary of the 1950s by James Stuart Olson (Greenwood Press, 2000)

James Dean: The Mutant King: A Biography by David Dalton (Chicago Review Press, 2001)

Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making Rebel Without a Cause by Lawrence Frascella and Al Weisel (Simon & Schuster, 2005)

Marlon Brando: A Biography by Patricia Bosworth (Viking Penguin, 2000)

Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon by Aram Goudsouzian (The University of North Carolina Press, 2004)

The Making of Rebel Without a Cause by Douglas L. Rathgeb (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2004)

Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks by Douglass K. Daniel (The University of Wisconsin Press, 2011)

Youth Culture in Global Cinema edited by Thomas Shary and Alexandra Seibel (University of Texas Press, 2007)

American Culture in the 1950s by Martin Halliwell (Edinburgh University Press, 2007)

American Education in Popular Media: From the Blackboard to the Silver Screen edited by S. G. Terzian and P. A. Ryan (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015)

Batman and Psychology: A Dark and Stormy Knight by Travis Langley (John Wiley & Sons, 2012)

Historical Dictionary of the 1950s by James Stuart Olson (Greenwood Press, 2000)

James Dean: The Mutant King: A Biography by David Dalton (Chicago Review Press, 2001)

Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making Rebel Without a Cause by Lawrence Frascella and Al Weisel (Simon & Schuster, 2005)

Marlon Brando: A Biography by Patricia Bosworth (Viking Penguin, 2000)

Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon by Aram Goudsouzian (The University of North Carolina Press, 2004)

The Making of Rebel Without a Cause by Douglas L. Rathgeb (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2004)

Tough as Nails: The Life and Films of Richard Brooks by Douglass K. Daniel (The University of Wisconsin Press, 2011)

Youth Culture in Global Cinema edited by Thomas Shary and Alexandra Seibel (University of Texas Press, 2007)

During the eight-year presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower, at the height of the Cold War, the United States was the most influential economic power in the world. Despite constant threats of Communism and nuclear annihilation, it looked as though the «American Dream» was finally a reality. People across the country were comfortably complacent, indulging in new cars, suburban houses, television sets and all sorts of new consumer goods. For the nation's adults, who still remembered the hardships of the Great Depression, life had never been better. However, for their teenage children, who had grown up during World War II, shielded from the most worrying of its effects, life was flawed by powerful feelings of alienation and anger.

During the eight-year presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower, at the height of the Cold War, the United States was the most influential economic power in the world. Despite constant threats of Communism and nuclear annihilation, it looked as though the «American Dream» was finally a reality. People across the country were comfortably complacent, indulging in new cars, suburban houses, television sets and all sorts of new consumer goods. For the nation's adults, who still remembered the hardships of the Great Depression, life had never been better. However, for their teenage children, who had grown up during World War II, shielded from the most worrying of its effects, life was flawed by powerful feelings of alienation and anger.

Fascinating analysis of the restless of the era and the three iconic films that capture that angst.

ReplyDeleteI love how you ended this post, by showing how hopeful and socially conscious the teens of this era turned out to be.

Thank you for joining the blogathon with this first-rate post.

Thank you so much. I'm glad you enjoyed reading it.

DeleteGreat post! It is weird and funny to see what the past generations worried about: comic books and Brando as bad influences? Come on!

ReplyDeleteYour post reminded me of an exploitation movie, almost a cautionary tale, called The Delinquents (1957), that, despite the moralistic tone, is very interesting.

Don't forget to read my contribution to the blogathon! :)

Cheers!

Le

http://www.criticaretro.blogspot.com.br/2015/06/1928-ao-redor-do-mundo-em-80-filmes.html

While The Wild One is highly regarded today, it was a failure upon its initial release, with critics finding it exploitative and overly violent. The film particularly horrified parents, who feared that it might set a bad example for their teenage children and lead to an imitation of crime. Kids, on the other hand, were fascinated by it and soon began emulating Brando's distinctive style.

ReplyDeleteThe Wild One also became a sensation with outlaw bikers, in particular the Hell's Angel's; Frank Sadilek, president of the San Francisco chapter, personally rode down to Los Angeles and visited Columbia Pictures to buy the shirt that Lee Marvin wore in the film, which he wore until it fell to pieces.