The Original Rebel Blogathon: John Garfield and the Hollywood Blacklist

With victory over the Germans within their grasp, the three Allied leaders held a conference in the Soviet town of Yalta in February 1945, for the purpose of discussing Europe's reorganization after World War II. American President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin decided that Germany — as well as its capital city, Berlin — would be divided into four occupied zones. Wanting to limit the Communist influence in Europe, Roosevelt and Churchill also called for elections in areas freed from the Germans. Stalin agreed to these terms, but no plans were made for when the elections would take place.

|

| (from left to right) Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin during the Yalta Conference; Berlin's four zones of occupation. |

After Roosevelt's death in April 1945 and the transfer of power to President Harry S. Truman, tensions began to mount between the United States and the Soviet Union. This was due to the fact that Stalin broke the agreement he had made in Yalta and installed Communist governments in several Eastern European countries, including Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Truman's response was to introduce a policy to contain the expansion of Communism to other countries, thus beginning a long rivalry between the world's two most powerful nations.

With the onset of the so-called Cold War, concerns about Communist infiltration of American society and government increased significantly, which contributed to the emergence of the second Red Scare (the first had taken place between 1917 and 1920, following the Bolshevik Russian Revolution). Prominent figures like Senator Joseph McCarthy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover soon joined Truman in conducting character investigations of «American Communists» (actual and alleged) and their roles in (real and imaginary) espionage, propaganda and subversion favouring the Soviet Union. Their anti-Communist campaigns resulted in a «witch hunt» that lasted from the late 1940s through the 1950s.

With the onset of the so-called Cold War, concerns about Communist infiltration of American society and government increased significantly, which contributed to the emergence of the second Red Scare (the first had taken place between 1917 and 1920, following the Bolshevik Russian Revolution). Prominent figures like Senator Joseph McCarthy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover soon joined Truman in conducting character investigations of «American Communists» (actual and alleged) and their roles in (real and imaginary) espionage, propaganda and subversion favouring the Soviet Union. Their anti-Communist campaigns resulted in a «witch hunt» that lasted from the late 1940s through the 1950s.

One of the main factors that contributed to the rise of the second Red Scare was the work of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Chaired by conservative Democrat Congressman Martin Dies Jr., the HUAC was initially established in May 1938, when membership in the Communist Party USA began to grow significantly. Its main purpose was to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees and any organization suspected of having Communist ties. When the United States and the Soviet Union joined forces to fight Nazi Germany during World War II, the American Communist Party gained more credibility and support, causing the HUAC to cease operations almost entirely. However, with the end of the war and Stalin's dominion over Eastern Europe, the HUAC was made a permanent committee, headed by Democratic Representative Edward J. Hart.

|

| (from left to right) Martin Dies Jr. in 1937; Dies proofing his letter replying to President Roosevelt's attack on the HUAC (October 26, 1938). |

In early 1947, J. Parnell Thomas replaced Hart as chairman of the HUAC and set out «to initiate an extensive and all-inclusive investigation of communistic activities and influences in the motion picture industry.» To that end, he travelled to Hollywood with a three-person subcommittee to ascertain whether Communist agents and sympathizers had been planting propaganda in American films. In May, he held a series of closed-door hearings at the Biltmore Hotel, where he informed reporters that the Screen Writers Guild was «lousy with Communists.» Among the people he interviewed, he found only 14 to be «friendly.»

Satisfied with the evidence he had uncovered, Thomas used the committee's subpoena power and summoned 19 «unfriendly witnesses» to testify at a public hearing in Washington D.C. on October 27. Immediately, a large group of Hollywood intellectuals and artists, led by directors John Huston and William Wyler and screenwriter Philip Dunne, joined forces in support of the Nineteen, founding the Committee for the First Amendment (CFA), which stressed the right of free speech. The team included such Hollywood stars as Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Katharine Hepburn, Danny Kaye, Gene Kelly, Myrna Loy, and John Garfield.

Satisfied with the evidence he had uncovered, Thomas used the committee's subpoena power and summoned 19 «unfriendly witnesses» to testify at a public hearing in Washington D.C. on October 27. Immediately, a large group of Hollywood intellectuals and artists, led by directors John Huston and William Wyler and screenwriter Philip Dunne, joined forces in support of the Nineteen, founding the Committee for the First Amendment (CFA), which stressed the right of free speech. The team included such Hollywood stars as Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Katharine Hepburn, Danny Kaye, Gene Kelly, Myrna Loy, and John Garfield.

Long involved in liberal politics, Garfield inevitably saw his name entangled in the Red Scare of the late 1940s and early 1950s. On October 27, he travelled with fellow members of the CFA to Washington D.C. to lobby Congress to get rid of HUAC, as well as lend moral support to the Nineteen. The CFA team was quite optimistic, since they had the support of the studio heads, whose spokesman, Eric Johnston, then the president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), was to set the tone at the hearings by protesting attempts to censure Hollywood. However, things did not proceed at all according to plan.

First, the CFA, fully expecting their press conference to take the limelight, was stunned when Thomas's announcement of a Soviet-Hollywood connection stole the headlines. They were further surprised when the committee called writer John Howard Lawson, instead of Johnston, to testify as first witness. The third and most profound shock was delivered by Johnston himself: instead of announcing his support for the CFA principles, he told the HUAC that he welcomed its investigations into Communism in Hollywood. With this, the CFA contingents left Washington D.C. thoroughly demoralized. Shortly thereafter, ten of the nineteen witnesses (including screenwriters Dalton Trumbo and Ring Lardner Jr., director Edward Dmytryk and Lawson himself) were held in contempt of Congress for refusing to testify and were subsequently fired by the studio heads. It was the beginning of the Hollywood blacklist.

In June 1950, the right-wing journal Counterattack published a pamphlet-style book titled Red Channels, naming 151 actors, writers, musicians, broadcast journalists and others in the context of Communist manipulation of the entertainment industry. Those identified in the tract were soon blacklisted by their employers and required to testify before the HUAC and «name names.» One of the artists listed in the Red Channels was John Garfield, who had previously been mentioned as a probable Communist sympathizer by California State Senator Jack Tenney. As such, Garfield received his subpoena on March 6, 1951 and appeared before the HUAC on April 23.

The HUAC also raised the question of Garfield's early affiliation with the Group Theatre, a New York City collective that had included blacklisted artists Lee J. Cobb, Frances Farmer and Howard Da Silva. The committee considered the Group Theatre to be «pretty well shot through with the philosophy of Communism,» but Garfield denied those allegations, claiming that he did not know a single Communist during all the time he was in New York. He continued to weave his way through the questions without bringing harm to anyone, ending his statement by asserting,

First, the CFA, fully expecting their press conference to take the limelight, was stunned when Thomas's announcement of a Soviet-Hollywood connection stole the headlines. They were further surprised when the committee called writer John Howard Lawson, instead of Johnston, to testify as first witness. The third and most profound shock was delivered by Johnston himself: instead of announcing his support for the CFA principles, he told the HUAC that he welcomed its investigations into Communism in Hollywood. With this, the CFA contingents left Washington D.C. thoroughly demoralized. Shortly thereafter, ten of the nineteen witnesses (including screenwriters Dalton Trumbo and Ring Lardner Jr., director Edward Dmytryk and Lawson himself) were held in contempt of Congress for refusing to testify and were subsequently fired by the studio heads. It was the beginning of the Hollywood blacklist.

|

| (from left to right) The Hollywood Ten in front of the District Building in Washington D.C. (October 1947); Trumbo at his HUAC hearing (October 28, 1947). |

In June 1950, the right-wing journal Counterattack published a pamphlet-style book titled Red Channels, naming 151 actors, writers, musicians, broadcast journalists and others in the context of Communist manipulation of the entertainment industry. Those identified in the tract were soon blacklisted by their employers and required to testify before the HUAC and «name names.» One of the artists listed in the Red Channels was John Garfield, who had previously been mentioned as a probable Communist sympathizer by California State Senator Jack Tenney. As such, Garfield received his subpoena on March 6, 1951 and appeared before the HUAC on April 23.

Technically classified as a friendly witness, Garfield assured the committee that he had never been «associated in any shape, way, or form» with the Communist Party and, like many of his colleagues, refused to name any names. When asked about his involvement with the Committee for the First Amendment during the 1947 hearings, he said,

«We were fighting on general principles. It had nothing to do with [the witnesses]. That is the whole point.»

The HUAC also raised the question of Garfield's early affiliation with the Group Theatre, a New York City collective that had included blacklisted artists Lee J. Cobb, Frances Farmer and Howard Da Silva. The committee considered the Group Theatre to be «pretty well shot through with the philosophy of Communism,» but Garfield denied those allegations, claiming that he did not know a single Communist during all the time he was in New York. He continued to weave his way through the questions without bringing harm to anyone, ending his statement by asserting,

«I have nothing to be ashamed of and nothing to hide. My life is an open book. [...] I am no Red. I am no 'pink.' I am no fellow traveller. I am a Democrat by politics, a liberal by inclination, and a loyal citizen of this country by every act of my life.»

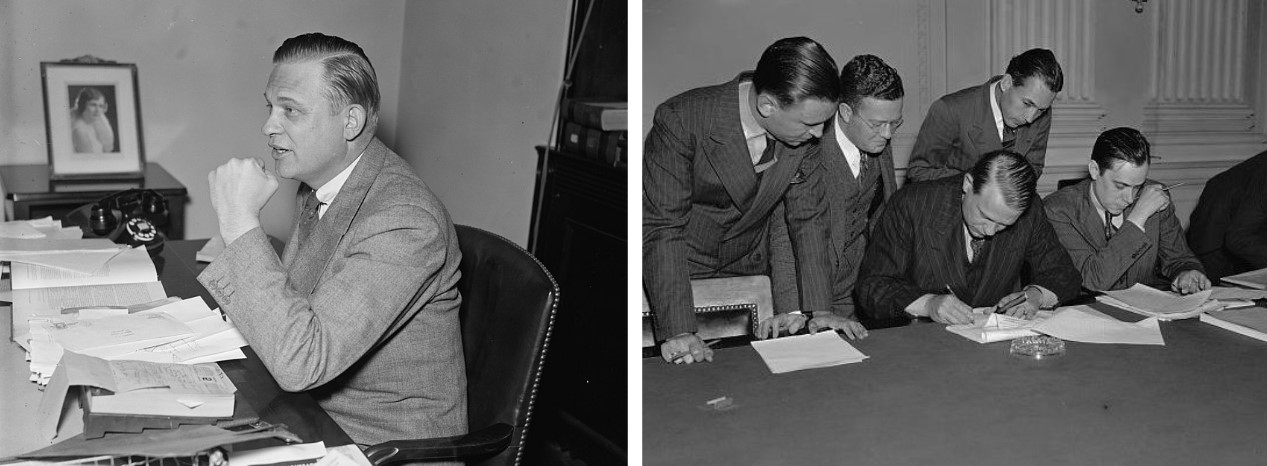

|

| (from left to right) John Garfield and other members of the CFA in Washington D.C. (October 1947); John Garfield during his HUAC hearing (April 23, 1951). |

Garfield was ecstatic that the HUAC «had not broken him.» The committee, on the other hand, was dissatisfied with his testimony and turned the matter over to the FBI, seeking grounds for a charge of perjury. With film work scarce because of the blacklist, Garfield returned to Broadway to star in a revival of Golden Boy, a drama written by former Communist Party member Clifford Odets, initially produced by the Group Theatre in 1937. Elia Kazan, who had also been a member of the Communist Party, was set to direct the play, but was forced to withdraw after receiving his own subpoena from the HUAC, being then replaced by Odets himself. Opening on March 12, 1952 at the ANTA Playhouse in New York, Golden Boy marked Garfield's first professional appearance since his testimony before the HUAC nearly a year earlier.

Although Golden Boy received good reviews from critics, Garfield's happiness over the play's success did not last long. First, Kazan rendered testimony that was damaging to several members of the Group Theatre, including Odets, who was subsequently scheduled to testify before the HUAC on May 19. Furthermore, the show closed on April 27 and, shortly thereafter, Garfield decided to move out of the family apartment in New York and checked into the Warwick Hotel. His wife, Roberta, did not approve of his plan to write an article for Look magazine in which he would affirm that he had been «duped» by Communist ideology. However, Garfield hoped that the piece, titled «I Was a Sucker for a Left Hook,» would redeem himself in the eyes of the blacklisters and restore both his career and his honour.

On Sunday, May 18, 1952, Garfield was seen wandering the streets of his old neighbourhood in the Bronx. On Monday, against his doctor's strict orders, he played tennis in the morning and baseball in the afternoon. Then he stayed up late playing poker with friends and attended to personal affairs on Tuesday, without getting much sleep. In the early evening, he met former actress Iris Whitney for dinner at Luchow's restaurant and afterwards they took a walk to Gramercy Park. When they arrived at her apartment, Garfield remarked that he felt «awful,» but refused to let Whitney call a doctor and went to bed instead. The following morning, May 20, Whitney found Garfield dead. A heart attack had taken his life at the age of 39.

In 1939, just after receiving his first Academy Award nomination — for his acclaimed supporting role in Michael Curtiz's Four Daughters (1938) — John Garfield declared,

Although Golden Boy received good reviews from critics, Garfield's happiness over the play's success did not last long. First, Kazan rendered testimony that was damaging to several members of the Group Theatre, including Odets, who was subsequently scheduled to testify before the HUAC on May 19. Furthermore, the show closed on April 27 and, shortly thereafter, Garfield decided to move out of the family apartment in New York and checked into the Warwick Hotel. His wife, Roberta, did not approve of his plan to write an article for Look magazine in which he would affirm that he had been «duped» by Communist ideology. However, Garfield hoped that the piece, titled «I Was a Sucker for a Left Hook,» would redeem himself in the eyes of the blacklisters and restore both his career and his honour.

|

| (from left to right) John Garfield and Shelley Winters in He Ran All the Way (1951), the actor's final film role; Playbill for the 1952 revival of Golden Boy. |

Meanwhile, with his name dragged through the mud, Garfield went into a tailspin. Blacklisted screenwriter Walter Bernstein remembered that, during this period,

«his face was lined and drawn, and he was drinking. He had always had the face of a bar mitzvah boy gone just wrong enough to enhance his appeal. Now he seemed old without having grown into it.»

On Sunday, May 18, 1952, Garfield was seen wandering the streets of his old neighbourhood in the Bronx. On Monday, against his doctor's strict orders, he played tennis in the morning and baseball in the afternoon. Then he stayed up late playing poker with friends and attended to personal affairs on Tuesday, without getting much sleep. In the early evening, he met former actress Iris Whitney for dinner at Luchow's restaurant and afterwards they took a walk to Gramercy Park. When they arrived at her apartment, Garfield remarked that he felt «awful,» but refused to let Whitney call a doctor and went to bed instead. The following morning, May 20, Whitney found Garfield dead. A heart attack had taken his life at the age of 39.

|

| John Garfield died from a heart attack at the young age of 39. |

In 1939, just after receiving his first Academy Award nomination — for his acclaimed supporting role in Michael Curtiz's Four Daughters (1938) — John Garfield declared,

«I must be in the theatre, otherwise I die. [...] No matter where I am or where I live, I will always act. Acting is my life.»

These words proved to be prophetic, for acting really was his life. Once he was cut off from the thing he loved so passionately, he wandered around in an aimless manner, unsure of which way to turn. But the sincere and intense performances that he contributed to American film and theatre stand as legacy for future generations. That was his gift, and nobody — not even the House Un-American Activities Committee — could ever take that away from him.

This post is my contribution to the John Garfield: The Original Rebel Blogathon hosted by Phyllis Loves Classic Films. To view all entries, click HERE.

______________________________________________

SOURCES: Dalton Trumbo: Blacklisted Hollywood Radical by Larry Ceplair and Christopher Trumbo (The University Press of Kentucky, 2015)

Hollywood Traitors: Blacklisted Screenwriters: Agents of Stalin, Allies of Hitler by Allan Ryskind (Regnery History, 2015)

Inside Out: A Memoir of the Blacklist by Walter Bernstein (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1996)

Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician by Barry Seldes (University of California Press, 2009)

John Garfield: The Illustrated Career in Films and on Stage by Patrick J. McGrath (McFarland & Company, Inc., 1993)

McCarthyism and the Red Scare: A Reference Guide by William T. Walker (ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2011)

McCarthyism: The Red Scare by Brian Fitzgerald (Compass Point Books, 2007)

Tough Without a Gun: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of Humphrey Bogart by Stefan Kanfer (Faber and Faber, 2001)

Acting really was his life. It saved him as a boy from turning to a life of crime. Wonderful post.

ReplyDeleteThanks so much for participating in this Blogathon :)

Thanks for very interesting post!!! Johnny allways was a legend!

ReplyDelete