Film Friday: Marty (1955)

In honour of Ernest Borgnine's 100th birthday, which was on Tuesday (January 24), this week on «Film Friday» I bring you the picture for which he is best known, which also happens to be the one that gave him the Academy Award for Best Actor.

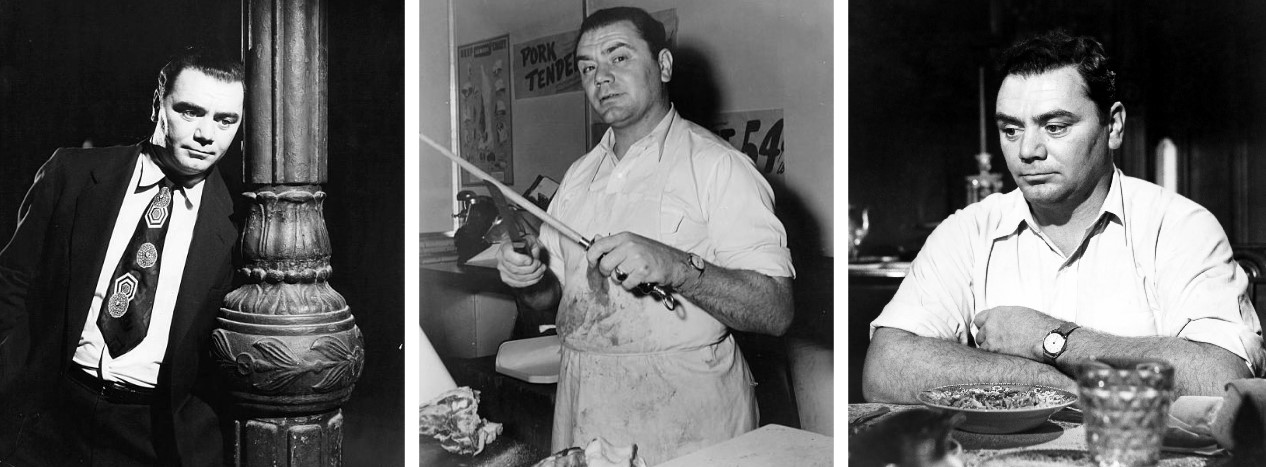

Directed by Delbert Mann, Marty (1955) tells the story of Marty Piletti (Ernest Borgnine), a good-natured but socially awkward Italian-American butcher who lives in The Bronx with his mother, Teresa (Esther Minciotti). Unmarried at 34, Marty faces constant badgering from family and friends to settle down, as all his brothers and sisters are already married and have children. One night, he goes to the Stardom Ballroom and meets Clara Snyder (Betsy Blair), a plain-looking 29-year-old high school chemistry teacher from Brooklyn who has been abandoned by her blind date. Mutually attracted, they spend the evening together dancing and walking the busy streets, and then Marty takes Clara home by bus, promising to call her at 2:30 the next afternoon.

Directed by Delbert Mann, Marty (1955) tells the story of Marty Piletti (Ernest Borgnine), a good-natured but socially awkward Italian-American butcher who lives in The Bronx with his mother, Teresa (Esther Minciotti). Unmarried at 34, Marty faces constant badgering from family and friends to settle down, as all his brothers and sisters are already married and have children. One night, he goes to the Stardom Ballroom and meets Clara Snyder (Betsy Blair), a plain-looking 29-year-old high school chemistry teacher from Brooklyn who has been abandoned by her blind date. Mutually attracted, they spend the evening together dancing and walking the busy streets, and then Marty takes Clara home by bus, promising to call her at 2:30 the next afternoon.

Meanwhile, Marty's busybody widowed aunt, Catherine (Augusta Ciolli), moves in to live with him and his mother. She warns Theresa, who is also a widow, that if Marty marries, she will be cast aside. Fearing that her son's romance could mean her abandonment, Theresa tells Marty not to bring Clara to the house again, saying that there are plenty of nice Italian girls in the neighbourhood. At the same time, Marty is disturbed to learn that his best friend Angie (Joe Mantell) has been deriding Clara for her plainness, describing her as a «dog.»

After his buddies inform him that it is bad for his reputation to go out with «dogs,» Marty gives in to peer pressure and does not call Clara, despite his earlier anticipation of seeing her again. However, as he and his friends face another tedious night at the local bar, Marty bursts out, calling them miserable, lonely and stupid. Realizing that he is giving up a woman whom he not only likes, but who also makes him happy, he rushes to a phone booth to call Clara. When Angie follows, Marty asks his pal when he is going to get married.

After his buddies inform him that it is bad for his reputation to go out with «dogs,» Marty gives in to peer pressure and does not call Clara, despite his earlier anticipation of seeing her again. However, as he and his friends face another tedious night at the local bar, Marty bursts out, calling them miserable, lonely and stupid. Realizing that he is giving up a woman whom he not only likes, but who also makes him happy, he rushes to a phone booth to call Clara. When Angie follows, Marty asks his pal when he is going to get married.

You don't like her, my mother don't like her, she's a dog and I'm a fat, ugly man! Well, all I know is that I had a good time last night! I'm gonna have a good time tonight! If we have enough good times together, I'm gonna get down on my knees and I'm gonna beg that girl to marry me! If we make a party on New Year's, I got a date for that party. You don't like her? That's too bad! (Marty Piletti)

A graduate of the City College of New York, Paddy Chayefsky began writing while recuperating from injuries sustained during World War II at the Army Hospital near Cirencester, England. his first effort was a musical play entitled No T.O. For Love, which was produced in 1945 by the Special Services Unit and ran for two years at Army bases throughout Europe, before starting a commercial run in London's West End. After the war, Chayefsky returned to New York and began working full-time on short stories and radio scripts, also serving as gag writer for radio personality Robert Q. Lewis. At the same time, he found steady employment as a television writer, making his debut with an adaptation of Budd Schulberg's novel What Makes Sammy Run? for The Philco Television Playhouse (1948-1955), a live anthology series produced by NBC.

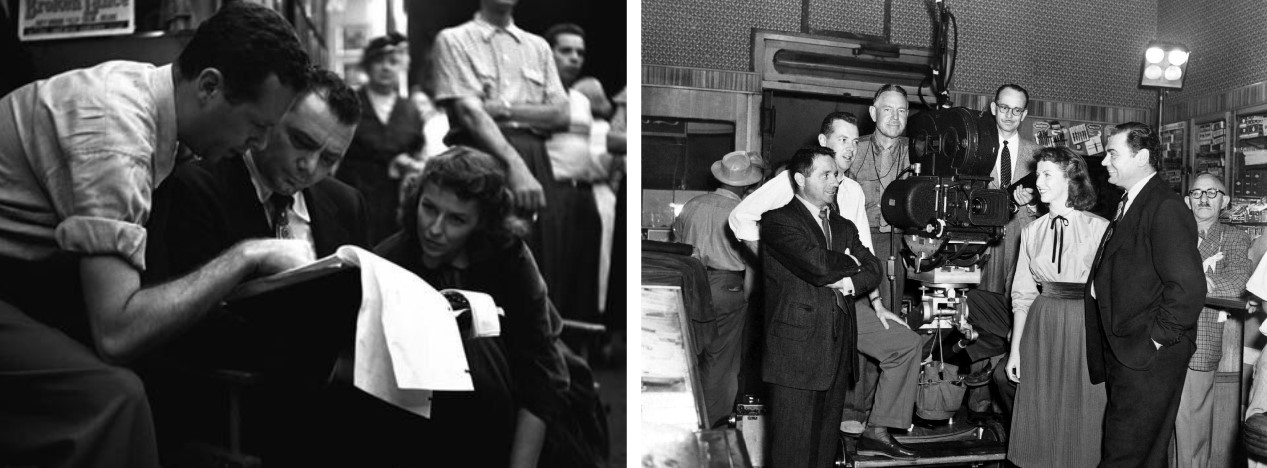

While rehearsing The Reluctant Citizen, his second script for the show, at the ballroom of the Abbey Hotel in New York, Chayefsky noticed that the staff was setting up for a lonelyhearts club meeting. He saw a sign that read, «Girls, Dance With the Man Who Asks You. Remember, Men Have Feelings Too,» which gave him the idea for a story about a young woman in a similar kind of setting. As he discussed it with director Delbert Mann, who was running the rehearsals of The Reluctant Citizen, Chayefsky decided that such a drama would be more interesting with a man as the central character rather than a woman. Mann then told him to pitch his idea to NBC producer Fred Coe, which Chayefsky did, simply by saying, «I want to do a play about a guy who goes to a ballroom.» Coe's answer was plain and short: «Go write it, pappy.»

While rehearsing The Reluctant Citizen, his second script for the show, at the ballroom of the Abbey Hotel in New York, Chayefsky noticed that the staff was setting up for a lonelyhearts club meeting. He saw a sign that read, «Girls, Dance With the Man Who Asks You. Remember, Men Have Feelings Too,» which gave him the idea for a story about a young woman in a similar kind of setting. As he discussed it with director Delbert Mann, who was running the rehearsals of The Reluctant Citizen, Chayefsky decided that such a drama would be more interesting with a man as the central character rather than a woman. Mann then told him to pitch his idea to NBC producer Fred Coe, which Chayefsky did, simply by saying, «I want to do a play about a guy who goes to a ballroom.» Coe's answer was plain and short: «Go write it, pappy.»

|

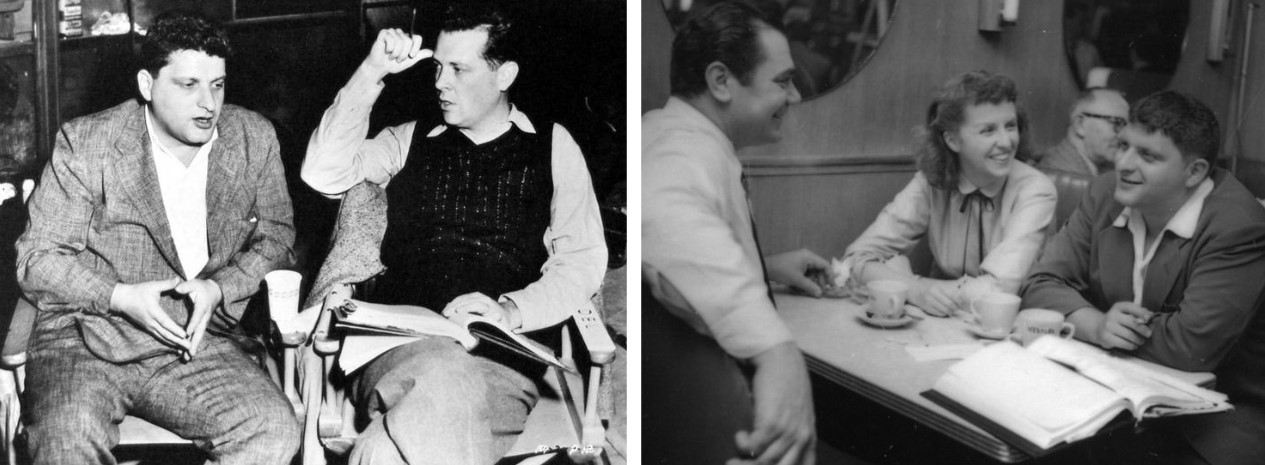

| (from left to right) Paddy Chayefsky and Delbert Mann discussing the script; Ernest Borgnine, Betsy Blair and Paddy Chayefsky during a break from filming. |

According to Chayefsky himself, he set out to write «the most ordinary love story in the world,» hoping it would revise Hollywood formulas by democratizing romance:

«I didn't want my hero to be handsome, and I didn't want the girl to be pretty. I wanted to write a love story the way it would literally have happened to the kind of people I know. I was, in fact, determined to shatter the shallow and destructive illusions — prospered by cheap fiction and bad movies — that love is simply a matter of physical attraction, that virility is manifested by a throbbing phallus, and that regular orgasms are all that's needed to make a woman happy.»

Chayefsky explorations of the «mundane, the ordinary, the untheatrical» love resulted in a 51-minute teleplay that dramatized a lonely butcher's break with neighbourhood values of friends and family in order to love a lonely schoolteacher. The story's original title, «Love Story,» was for some reason deemed unacceptable by NBC, who requested a name change. It was ultimately shown on May 14, 1953 on The Philco Television Playhouse under the title «Marty,» with Rod Steiger in the title role, Marty Piletti, and Nancy Marchand, in her television debut, as Clara Snyder, the plain-looking high school chemistry teacher with whom he falls in love.

|

| Rod Steiger and Nancy Marchand in the original television production of Marty. |

Directed by Mann, Marty was such a critical and popular success that it immediately caught the attention of Hollywood producers. Former agent Harold Hecht and actor Burt Lancaster, who had formed an independent production company in 1948, purchased the rights to Chayefsky's story, signing a distribution deal with United Artists in February 1954.

Not trusting the Hollywood system, Chayefsky made unprecedented demands in his contract. He wanted to write the film script himself and have complete control over it, as well as casting approval and a directing job for Mann, who had never worked in motion pictures before. Surprisingly, Hecht and Lancaster agreed to all of his demands and the film was subsequently green-lighted. In order to expand his 51-minute teleplay to feature length, Chayefsky added scenes about Marty's job as a butcher and developed his relationship with his Italian-born mother and sister, in addition to making the leading lady's role somewhat larger.

Not trusting the Hollywood system, Chayefsky made unprecedented demands in his contract. He wanted to write the film script himself and have complete control over it, as well as casting approval and a directing job for Mann, who had never worked in motion pictures before. Surprisingly, Hecht and Lancaster agreed to all of his demands and the film was subsequently green-lighted. In order to expand his 51-minute teleplay to feature length, Chayefsky added scenes about Marty's job as a butcher and developed his relationship with his Italian-born mother and sister, in addition to making the leading lady's role somewhat larger.

Steiger was approached by Hecht and Lancaster to reprise his role in the film version of Marty, but he declined, as he was not willing to sign the long-term contract that came with to the offer. In need to find another Marty, Mann turned to his friend Robert Aldrich, who was then directing Vera Cruz (1954) with Lancaster, Gary Cooper and newcomer Ernest Borgnine. After reading the script, Aldrich said to Mann, «I know only one man who could do it: Ernie Borgnine.»

A veteran of World War II, Borgnine studied drama on the GI Bill and began his acting career on stage, making his Broadway debut in 1949 in the Pulitzer Prize-winning play Harvey. In the early 1950s, he transitioned to television, working with Mann in episodes of The Philco Television Playhouse, as well as of Goodyear Television Playhouse (1951-1957), another anthology series produced by NBC. His performances on the small screen soon led to a substantial supporting role opposite Lancaster in Fred Zinnemann's Oscar-winning film From Here to Eternity (1953), wherein he played a sadistic Army sergeant.

A veteran of World War II, Borgnine studied drama on the GI Bill and began his acting career on stage, making his Broadway debut in 1949 in the Pulitzer Prize-winning play Harvey. In the early 1950s, he transitioned to television, working with Mann in episodes of The Philco Television Playhouse, as well as of Goodyear Television Playhouse (1951-1957), another anthology series produced by NBC. His performances on the small screen soon led to a substantial supporting role opposite Lancaster in Fred Zinnemann's Oscar-winning film From Here to Eternity (1953), wherein he played a sadistic Army sergeant.

Lancaster immediately approved the casting of Borgnine, who was more than honoured to be asked to play the title character in Marty, his first leading role. According to the actor, he «went absolutely blank» when Hecht offered him the part. He remembered,

«I didn't say 'thanks' or 'great, call my agent.' What came from my mouth was, 'You have faith in me?' [...] As I walked from his office with a bounce in my step, I looked up to heaven and gave a silent prayer of thanks.»

Although Hecht and Lancaster were sure that Borgnine was right for the role, Mann hesitated, as the 37-year-old actor was until then primarily known for playing villainous roles. After he read for the part, however, all of Mann's initial doubts dissipated. Borgnine, an Italian-American just like Marty Piletti, later recalled his audition:

«I turned away because I had started to cry. [...] When I turned back to Paddy, who was playing the mother, I saw he was crying too. And out of the corner of my eye, I could see Del was also close to tears. That gave me the most wonderful feeling in my life; to think I had accomplished something that could affect people this way.»

Originally, Nancy Marchand was slated to make her motion picture debut reprising her role as Clara Snyder, but Betsy Blair showed interest in the part and started campaigning hard for it. Hecht and Lancaster, as well as United Artists, initially refused to cast her because she had been blacklisted for her Marxist and Communist sympathies. Hearing of this, Blair's husband at the time, song-and-dance man Gene Kelly, swore he would never work for any of them if they did not give his wife the role. Moreover, Kelly got Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, his home studio, to help him exert pressure by refusing to star in It's Always Fair Weather (1955) for them. Finally, MGM head of production Dore Schary contacted the American Legion to personally vouch for Blair, effectively removing her from the blacklist and allowing her to play Clara in Marty.

With Joe Mantell, Esther Minciotti and Augusta Ciolli re-creating their roles from the original teledrama, Marty began filming in early September 1954 with location shooting in The Bronx. Among the landmarks used in the picture are the Grand Concourse thoroughfare and the IRT Third Avenue El, an elevated railway line that closed down in the 1970s. In early November, the company convened at the Samuel Goldwyn Studios in Hollywood to shoot interior scenes. Halfway through production, United Artists threatened to pull the plug on the project because other Hecht-Lancaster films were running over budget. According to Borgnine, the studio's accountants eventually saved the picture by pointing out that under the new tax laws, they had to complete Marty and screen it at least once before they could write it off as a tax loss.

The first major Hollywood film adapted from a television play, Marty premiered on April 11, 1955 at the Sutton Theatre in New York, normally a venue where art-house productions were shown. Bernie Kambler, the head of the publicity department of the Hecht-Lancaster East Coast offices, conducted a personal campaign for the film, setting up private screenings and convincing major press outlets to feature it positively. Kambler's most successful stunt was getting influential columnist and radio commentator Walter Winchell to hail the film as one of the biggest sleeper hits in Hollywood history. Reportedly, more money ($400,000) was spent on advertising Marty than the film's initial production costs of a mere $343,000.

The slow build on viewership for Marty began with strong reviews from critics. Ronald Holloway of Variety called it a «warm, human, sometimes sentimental and an enjoyable experience,» while the notoriously acidic Bosley Crowther of The New York Times described it as «a warm and winning film, full of the sort of candid comment on plain, drab people that seldom reaches the screen.» The two leads were widely applauded for their performances, with Borgnine being universally singled out for praise for his versatility as an actor. In May 1955, Marty won the first Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, which resulted in more press and more profits at the box-office. By the end of that year, the picture had earned $2,000,000 in domestic rentals alone, making it one of the biggest moneymakers of 1955.

The slow build on viewership for Marty began with strong reviews from critics. Ronald Holloway of Variety called it a «warm, human, sometimes sentimental and an enjoyable experience,» while the notoriously acidic Bosley Crowther of The New York Times described it as «a warm and winning film, full of the sort of candid comment on plain, drab people that seldom reaches the screen.» The two leads were widely applauded for their performances, with Borgnine being universally singled out for praise for his versatility as an actor. In May 1955, Marty won the first Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, which resulted in more press and more profits at the box-office. By the end of that year, the picture had earned $2,000,000 in domestic rentals alone, making it one of the biggest moneymakers of 1955.

|

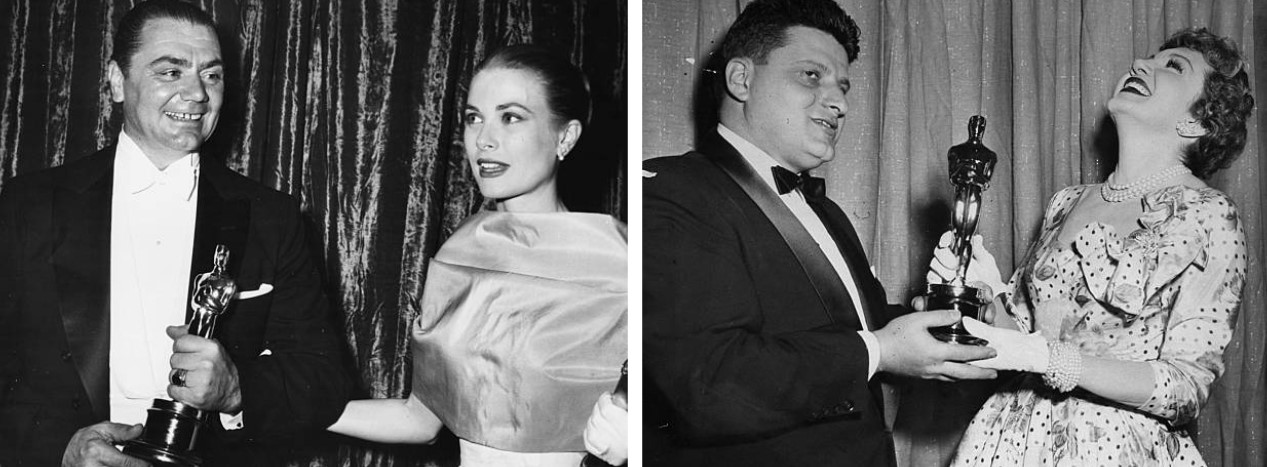

| (from left to right) Ernest Borgnine with his Oscar and presenter Grace Kelly; Paddy Chayefsky accepting his Oscar from Claudette Colbert. |

At the 28th Academy Awards ceremony held on March 21, 1956 at the RKO Pantages Theatre in Los Angeles, Marty won the coveted statuette for Best Picture, as well as Best Director, Best Actor (Borgnine) and Best Original Screenplay. Borgnine's fellow nominees were former Best Actor winners James Cagney and Spencer Tracy, with whom he had appeared in Bad Day at Black Rock (1953), James Dean, who had died in a car accident six months before the ceremony, and Frank Sinatra, whose acclaimed performance in From Here to Eternity had earned him an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor two years earlier. In addition, Marty received nominations for Best Supporting Actor (Joe Mantell), Best Supporting Actress (Betsy Blair), Best Art Direction (Black-and-White) and Best Cinematography (Black-and-White). Mantell lost to Jack Lemmon for Mister Roberts (1955), while Blair lost to Joe Van Fleet for East of Eden (1955). The Rose Tattoo (1955) won both Best Art Direction and Best Cinematography.

______________________________________________

SOURCES: Ernest Borgnine: My Autobiography by Ernest Borgnine (Aurum Press, 2013)

Storytellers to the Nation: A History of American Television Writing by Tom Tempel (Syracuse University Press, 1996)

The Collected Works of Paddy Chayefsky: The Television Plays by Paddy Chayefsky (Applause Books, 1994)

Understanding Love: Philosophy, Film, and Fiction edited by Susan Wolf and Christopher Grau (Oxford University Press, 2014)

Comments

Post a Comment