Happy 100th Birthday, Van Johnson!

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's «Golden Boy,» also known as Van Johnson, was born Charles Van Dell Johnson on August 25, 1916 in Newport, Rhode Island. He was the only child of Loretta (neé Snyder), a housewife from a Pennsylvania Dutch background, and Charles E. Johnson, a plumber and later real-estate salesman of Swedish descent. From the beginning, the free-spirited Loretta felt miserable in her marriage to Charles, a tough-minded, pragmatic man who valued thrift over material comfort. The arrival of a son merely added more pressure to the young couple's dismal relationship, and ultimately drove Loretta to alcoholism.

When Van was only three years old, Loretta abandoned the family and fled to Brooklyn, New York in pursuit of a livelier and more fulfilled existence. Van would not see her mother again until he was in his late teens. Commenting on his parents' divorce years later, Van said,

«I was too young to comprehend it then and today I deliberately don't try.»

After Loretta left, Van continued to reside in Newport with his father and grandmother, who were both strict disciplinarians. Young Van was instructed in good manners, neatness of appearance, honesty and respect for older people. As he grew up, he was expected to take care of his own clothes, as he was instilled from early on with a keen sense of duty and taught the importance of production work. Van respected and admired his father, but he also feared him. Charles later said,

«There was a rumour around that I was a strict sourpuss father. I was strict about a few things, and one was [Van's] health. I never spanked him in my life. He was my buddy [...] and all it took was a hard look to straighten him out.»

However, the austere environment in which Van was raised created a long-lasting emotional distance between him and his father. Charles did not believe in expressing personal feelings, teaching his young son to divert displays of joy, anger and sorrow into some demonstrative behaviour and not to act on impulse. For a sensitive, introverted child like Van, this led to insecurity and repression. Early in his Hollywood career, he confessed,

«I've often wished my childhood had been a little different [and] that I had a mother's guidance like other boys.»

When he entered Cranston-Calvert Elementary School, Van had good grades, as his teachers «made me interested in what I was supposed to learn.» But the red-headed, freckled-faced kid was shy with girls and a loner. For a special outing one day, Charles took his son to nearby Providence to see a circus, an excursion that made Van decide that he wanted to be in show business, preferably as a trapeze artist or a tightrope walker. His determination was such that he began doing odd jobs after school, including mowing laws and delivering groceries, so that he could earn enough money to buy a trapeze and rings. Van later explained,

«It wasn't that I loved work so much, but that I loved possessions more. Dad had one rule: I could have what I wanted if I earned the price of it myself.»

Once he purchased the trapeze and rings, he suspended them from a large tree limb in the backyard and practice on them for hours.

Van's interest in the world of entertainment broadened when he discovered silent pictures. The first film he remembered seeing was The Galloping Fish (1924), a comedy directed by Del Andrews, starring Louise Fazenda and Sydney Chaplin. He would most of his free time at the movies, mesmerized by the magical world he secretly longed to join. He also started reading fan magazines and cut out pictures of his favourite stars, which he would then pin to the wall of his room. Soon, it became obvious to his family and schoolmates that Van had a desire to turn himself into a performer. By the time he was eight years old, he and his friends were putting on shows in the Johnson's backyard for the neighbors, charging a penny for admission. However, the humorless Charles did not support his son's ambition to pursue a career in show business. «The only stage you'll ever be on will be a [house] painter's stage,» he would snort.

Van's interest in the world of entertainment broadened when he discovered silent pictures. The first film he remembered seeing was The Galloping Fish (1924), a comedy directed by Del Andrews, starring Louise Fazenda and Sydney Chaplin. He would most of his free time at the movies, mesmerized by the magical world he secretly longed to join. He also started reading fan magazines and cut out pictures of his favourite stars, which he would then pin to the wall of his room. Soon, it became obvious to his family and schoolmates that Van had a desire to turn himself into a performer. By the time he was eight years old, he and his friends were putting on shows in the Johnson's backyard for the neighbors, charging a penny for admission. However, the humorless Charles did not support his son's ambition to pursue a career in show business. «The only stage you'll ever be on will be a [house] painter's stage,» he would snort.

During his years at John Clarke Middle School, Van attended whatever stage plays came to Newport and «decided I wanted to be one those people up there entertaining people.» To his father's irritation, Van used the three dollars he was earning every month from doing odd jobs to enroll himself in Dorothy Gladding's dancing school, where he quickly showed a talent for tap, adagio, soft-shoe and ballroom dancing. Before long, Van was performing with an amateur group at social clubs, church gatherings and any other place that requested free entertainment. He even created his own song-and-dance routine, which proved a big hit in the annual variety show at the Colonial Theatre, Newport's main vaudeville house.

Meanwhile, Van found time to take violin lessons, and he played in the orchestra at Rogers High School during his last three years there. He was also in the Dramatic Society in his freshman year, although he never got a part in any school plays. «I chewed up plenty of scenery at the tryouts,» he remembered, «but I could never make the grade.» After repeated readings, the teacher in charge of the school plays told him most emphatically, «You'll never make it as an actor.»

Over six feet tall and nicknamed «Red,» Van was miserable throughout his first two years of high school. Painting was the only class he truly enjoyed, and he showed no interest in ever going to college. He was never part of the elite crowd and he did not date, finding relief only by losing himself in the fantasies he saw on stage and screen. By the time he became a junior, however, Van had shed some of his shyness and became more self-confident, mainly through the skill he demonstrated on the dance floor. He took his first girl to a dance that year and soon became a popular partner at proms and social gatherings where music was played.

Van graduated from Rogers High School in the spring of 1934. The class prophecy for him in the yearbook read: «Van Johnson will be a dancer, / For his snake hips he'll be known, / You'll soon see him performing / Before the English heir to the throne.» For a year after graduation, Van joined his father in the plumbing business, working as an accountant and stenographer. However, he found his job extremely dull and continued to dream, as he put it, of «something shadowy, dreamy, and dramatic.» The movies remained Van's primary source of solace and excitement. Spencer Tracy became his favourite leading man, and he found the Busby Berkeley musicals and those featuring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dazzling.

Van graduated from Rogers High School in the spring of 1934. The class prophecy for him in the yearbook read: «Van Johnson will be a dancer, / For his snake hips he'll be known, / You'll soon see him performing / Before the English heir to the throne.» For a year after graduation, Van joined his father in the plumbing business, working as an accountant and stenographer. However, he found his job extremely dull and continued to dream, as he put it, of «something shadowy, dreamy, and dramatic.» The movies remained Van's primary source of solace and excitement. Spencer Tracy became his favourite leading man, and he found the Busby Berkeley musicals and those featuring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers dazzling.

In the summer of 1935, Van took a job as a waiter and part-time cook at a clam restaurant, where he befriended an attractive, red-headed girl named Lois Sanborn. Ambitious and worldly-wise, Lois believed that people should try to fulfill their dreams and encouraged Van to pursue his. If show business was his ambition, she told him, then he must go to New York. Although he was eager to leave Newport, Van was unwilling to leave his father, who had no other family now that his grandmother was gone. However, over the summer he warmed up to the idea of moving away; Hollywood was his goal, but New York was closer.

That fall, Van told his father that he wanted to move to New York to find work on the stage. Charles reluctantly agreed to let him go, but told him to come home when he had gotten his fill of «such silly notions.» As long as Van could support himself, his father said, he was free to live the life he wanted. Van left Newport in September 1935, wearing a brown sports coat over white flannel pants and an old straw hat, with five dollars in his pocket. He had just turned 19 years old.

That fall, Van told his father that he wanted to move to New York to find work on the stage. Charles reluctantly agreed to let him go, but told him to come home when he had gotten his fill of «such silly notions.» As long as Van could support himself, his father said, he was free to live the life he wanted. Van left Newport in September 1935, wearing a brown sports coat over white flannel pants and an old straw hat, with five dollars in his pocket. He had just turned 19 years old.

Within weeks of his arrival in New York, Van realized that competition for jobs in the entertainment industry was fierce and he remained unemployed for months. One evening in December, just as he was about to wire his father for money to return home, Van walked past a talent agency and noticed a light still on. He went inside and found an agent's wife waiting for her husband in an outer office. Van's smile was enough to convince the woman to introduce him to her husband, Murray Phillips, who asked the aspiring entertainer what shows he had been in. Van lied and said he had played juvenile leads in stock in Newport, done understudying in New York and was a seasoned song-and-dance man. Phillips was not fooled, but he told Van to go the next morning to the Cherry Lane Theatre in Greenwich Village, where he would be casting an intimate revue. At the audition, he sang Duke Ellington's 1934 composition «(In My) Solitude,» which, to his amazement, earned him a place singing and dancing in Phillips's show. The off-Broadway production was called Entre Nous and it lasted four weeks.

Although Entre Nous proved that Van was a skilled performer, offers for new shows were not forthcoming. With his money running out, he accepted an offer to tour as a substitute dancer with a theatre troupe bound for New England. He welcomed the money and the experience, but he stayed with the company only for a short while. Back in New York, he continued auditioning for every part available, finding once again that competition was extremely strong. One day, on his way home from an audition for a dancing job he did not get, he heard a piano in a rehearsal hall and stepped inside to see what was going on. A man on the stage noticed Van standing around with his tap shoes and assumed that the youth had been sent by an agent in answer to a casting call. The man motioned for Van to come forward and told him to get into his tap shoes and show what he could do. «I felt as if someone had run a blow torch up and down my spine,» Van later recalled. Sensing that this was his big moment, he performed double time, triple time and wing time. «Nobody had to give me a pep talk to make me knock myself out,» Van said. «I was kicking through with everything I had.»

Although Entre Nous proved that Van was a skilled performer, offers for new shows were not forthcoming. With his money running out, he accepted an offer to tour as a substitute dancer with a theatre troupe bound for New England. He welcomed the money and the experience, but he stayed with the company only for a short while. Back in New York, he continued auditioning for every part available, finding once again that competition was extremely strong. One day, on his way home from an audition for a dancing job he did not get, he heard a piano in a rehearsal hall and stepped inside to see what was going on. A man on the stage noticed Van standing around with his tap shoes and assumed that the youth had been sent by an agent in answer to a casting call. The man motioned for Van to come forward and told him to get into his tap shoes and show what he could do. «I felt as if someone had run a blow torch up and down my spine,» Van later recalled. Sensing that this was his big moment, he performed double time, triple time and wing time. «Nobody had to give me a pep talk to make me knock myself out,» Van said. «I was kicking through with everything I had.»

|

| Broadway playbill for Leonard Sillman's New Faces of 1936. |

As it turned out, the man was Leonard Stillman, a noted Broadway producer who had already given an early career boost to actors Tyrone Power and Henry Fonda, comedienne Imogene Coca and dancer and future Hollywood director Charles Walters. Sillman was then in the second week of rehearsing New Faces of 1936 and needed a replacement for a male dancer who had sprained an ankle. The producer remembered Van as «a husky blond boy,» so shy that he blushed and stammered when he talked. «He showed me some of his light fantastic stuff,» Sillman recalled, «and he was unquestionably a brilliant hoofer.» Sillman hired Van on the spot and told him to start learning the routines, which he did in short order. Premiering at the Vanderbilt Theatre in Manhattan in May 1936, New Faces was a hit among audiences and received excellent reviews from critics. Van stayed with the revue through its entire 40-week run.

|

| LEFT: Mary Jane Walsh and Van Johnson (2L) performing with others in Too Many Girls. RIGHT: Van Johnson and June Havoc in Pal Joey. |

In the late summer of 1939, after working in hotel resorts and nightclubs, Van was cast in Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart's musical comedy Too Many Girls, directed by George Abbott. He appeared in the chorus as a college boy and served as understudy for all three male leads: Desi Arnaz, Eddie Bracken and Richard Kollmar, the latter of whom he eventually replaced. The following year, Abbott was hired by RKO to helm a screen adaptation of Too Many Girls as a vehicle for Lucille Ball. The director brought in Arnaz and Bracken to reprise their Broadway roles and also found a bit part for Van, who made his motion picture debut in an uncredited role as a college boy. Shortly after the release of Too Many Girls (1940), Abbott hired Van as a chorus boy and Gene Kelly's understudy in the new Rodgers and Hart's show, Pal Joey, a controversial musical based on a series of short stories written by John O'Hara.

The success of Pal Joey earned Van a contract at Warner Bros. and the male lead in Murder in the Big House (1942), a low-budget feature co-starring Faye Emerson. His role as a reporter investigating the murder of a death-row inmate required him to dye his eyebrows and hair black. Soon, it became evident that Van's all-American good looks and easy demeanour were ill-suited to the gritty melodramas Warners made at the time, which led the studio to drop him when his six-month contract ended. Discouraged, Van prepared to move back to New York.

Having heard that he was about to leave Hollywood, newlyweds Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, whom Van had befriended during the making of Too Many Girls, invited him to a farewell dinner at Chasen's, a popular restaurant among the Hollywood crowd. Seated at the next table happened to be Bill Grady, for many years the head of talent at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Through Ball's intercession, Grady agreed to schedule a screen test for Van at MGM studios in Culver City. A few days later, he tested opposite Donna Reed, a newly signed MGM player, and a contract was quickly negotiated for Van, with his salary starting at $350 a week. As part of the «grooming process,» he was provided with classes in acting, speech and diction.

Having heard that he was about to leave Hollywood, newlyweds Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, whom Van had befriended during the making of Too Many Girls, invited him to a farewell dinner at Chasen's, a popular restaurant among the Hollywood crowd. Seated at the next table happened to be Bill Grady, for many years the head of talent at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Through Ball's intercession, Grady agreed to schedule a screen test for Van at MGM studios in Culver City. A few days later, he tested opposite Donna Reed, a newly signed MGM player, and a contract was quickly negotiated for Van, with his salary starting at $350 a week. As part of the «grooming process,» he was provided with classes in acting, speech and diction.

After small roles in Somewhere I'll Find You (1942) and The War Against Mrs. Hadley (1942), Van was chosen to replace Lew Ayres in the continuation of the popular Dr. Kildare series. Beginning with Dr. Gillespie's New Assistant (1942), he reprised his role as Dr. Randall «Red» Adams in three other installments. Van then reunited with Gene Kelly in Pilot #5 (1943) and received a supporting role in The Human Comedy (1943), before earning his big break in A Guy Named Joe (1943), a wartime drama starring his idol Spencer Tracy and Irene Dunne.

Midway through the production of A Guy Named Joe in 1943, Van was involved in a serious car accident that left him with a metal plate in his forehead and a number of scars on his face that the plastic surgery of the time could not completely conceal (he used heavy makeup to hide them for years). MGM wanted to replace him, but Tracy insisted that Van be allowed to finish the picture, despite his long absence. The injury exempted Van from military service in World War II.

Midway through the production of A Guy Named Joe in 1943, Van was involved in a serious car accident that left him with a metal plate in his forehead and a number of scars on his face that the plastic surgery of the time could not completely conceal (he used heavy makeup to hide them for years). MGM wanted to replace him, but Tracy insisted that Van be allowed to finish the picture, despite his long absence. The injury exempted Van from military service in World War II.

With many actors serving in the armed forces, the accident greatly benefited Johnson's career. He later said,

«There were five of us. There was Jimmy Craig, Bob Young, Bobby Walker, Peter Lawford, and myself. All tested for the same part all the time.»

Johnson was very busy, often playing soldiers:

«I remember [...] finishing one Thursday morning with June Allyson and starting a new one Thursday afternoon with Esther Williams. I didn't know which branch of the service I was in!»

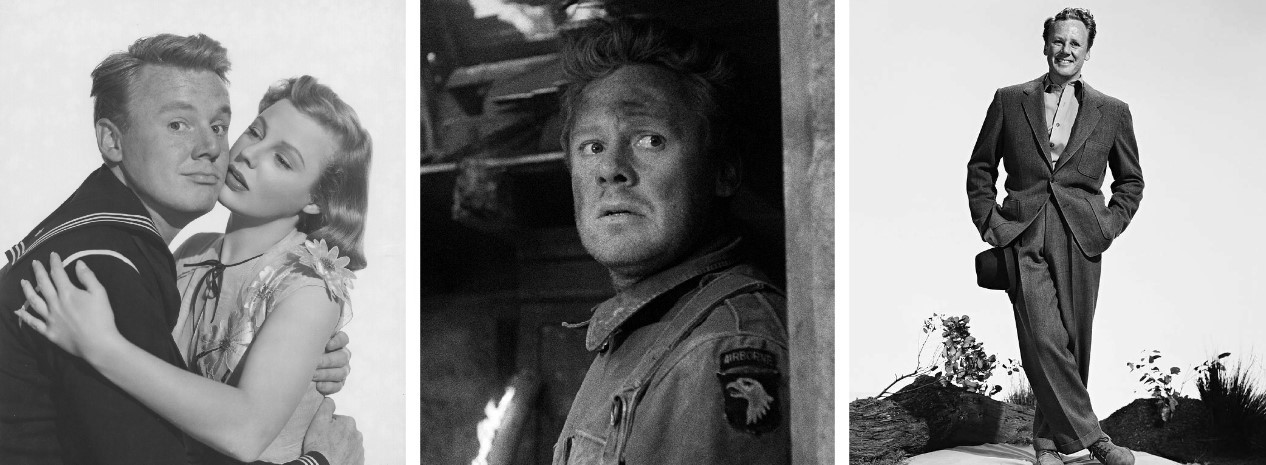

MGM built up his image as the all-American boy in war dramas and musicals, with his most notable starring role being that of Ted Lawson in Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944), which told the story of the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo in April 1942, as retaliation for the attack on Pearl Harbor.

|

| LEFT: Van Johnson with Spencer Tracy and Phyllis Thaxter in a publicity still for Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo. RIGHT: Van and Robert Mitchum in the same film. |

In 1945, Van tied with Bing Crosby as the top box office stars chosen yearly by the National Association of Theater Owners. But he fell off the list as other top Hollywood stars returned from wartime service. As a musical comedy performer, Van appeared in five films each with Allyson and Williams. His films with Allyson included the musical Two Girls and a Sailor (1944) and the mystery farce Remains to Be Seen (1953). With Williams, he made the comedy Easy to Wed (1946), which also featured Ball and his old friend Keenan Wynn, and the musical comedy Easy to Love (1953). He also starred with Judy Garland in In the Good Old Summertime (1949), and re-teamed with Gene Kelly as the sardonic second lead of Brigadoon (1954). Johnson continued to appear in war movies after the war ended, including Battleground (1949), an account of the Battle of the Bulge, and Go for Broke! (1951), in which he played an officer leading Japanese-American troops of the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Europe.

With the advent of television in the early 1950s, MGM began suffering financially and, as a result, the studio began streamlining its roster of stars and contract players. Johnson was one of several major stars dropped by MGM in 1954. His final appearance for the studio was in The Last Time I Saw Paris (1954) with Elizabeth Taylor and Walter Pidgeon.

Moving to Columbia, Van enjoyed critical acclaim for his performance as Lt. Steve Maryk in The Caine Mutiny (1954). He refused to allow concealment of his facial scars when being made up as Maryk, believing they enhanced the character's authenticity. One commentator noted years later that «Humphrey Bogart and José Ferrer chomp up all the scenery in this maritime courtroom drama, but it's Johnson's character, the painfully ambivalent, not-too-bright Lieutenant Steve Maryk, who binds the whole movie together.» TIME commented that Van Johnson «was a better actor than Hollywood usually allowed him to be.»

Moving to Columbia, Van enjoyed critical acclaim for his performance as Lt. Steve Maryk in The Caine Mutiny (1954). He refused to allow concealment of his facial scars when being made up as Maryk, believing they enhanced the character's authenticity. One commentator noted years later that «Humphrey Bogart and José Ferrer chomp up all the scenery in this maritime courtroom drama, but it's Johnson's character, the painfully ambivalent, not-too-bright Lieutenant Steve Maryk, who binds the whole movie together.» TIME commented that Van Johnson «was a better actor than Hollywood usually allowed him to be.»

|

| LEFT: Van Johnson and Elizabeth Taylor in The Last Time I Saw Paris. RIGHT: Van Johnson as Lieutenant Steve Maryk in The Caine Mutiny. |

As middle-age dawned, Van's features became heavier and acquired a slightly worried look, but he did well in offbeat entries while free-lancing. His films during this period include The End of the Affair (1955), with Deborah Kerr, Miracle in the Rain (1956), co-starring Jane Wyman, 23 Paces to Baker Street (1956), opposite Vera Miles, and the British-made Beyond This Place (1959). He was also a regular in homes during the Thanksgiving holidays, thanks to his appearance as the title character in The Pied Piper of Hamelin (1957), a musical film made by NBC, based on the famous poem of the same name by Robert Browning.

|

| LEFT: Van Johnson and Vera Miles in 23 Paces to Baker Street. RIGHT: Lobby card for The Pied Piper of Hamelin, the first film ever made for television. |

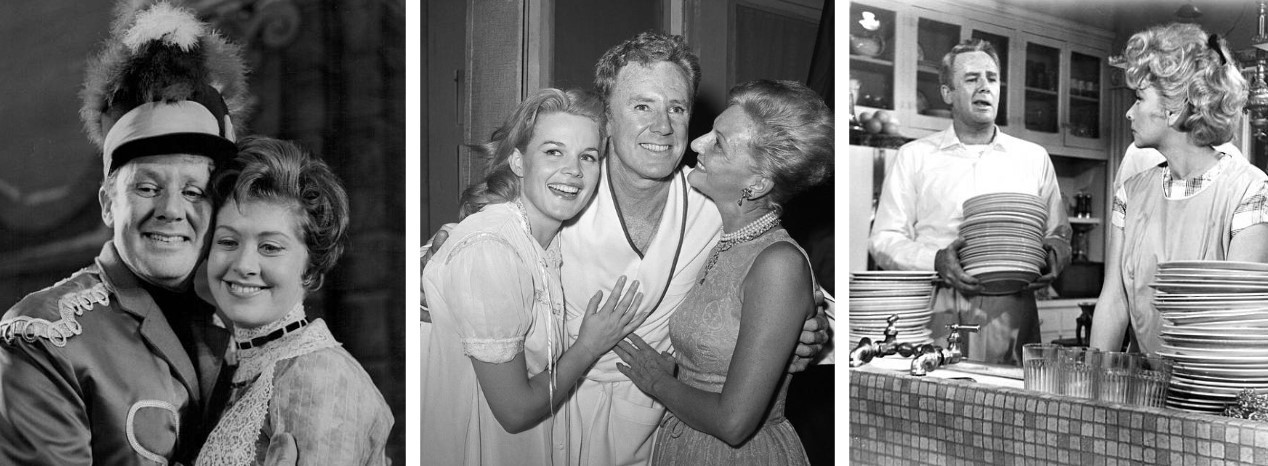

With the coming of the 1960s, Van found it increasingly harder to find good movie roles. He continued to appear on television and worked frequently in nightclubs and stage musicals. In 1961, he travelled to England to star in Harold Fielding's production of The Music Man at the Adelphi Theatre in London. The show enjoyed a successful run of almost a year, with Van playing the leading role of con man Harold Hill to great acclaim. He also appeared in Garson Kanin's Come on Strong at the Morosco Theatre on Broadway in 1962.

Operations for skin cancer and the removal of a lymph gland removed Van from public life in the mid 1960s, but he was back on television and in feature films by the end of the decade. Now established as an affable supporting star, he appeared in family comedies like Yours, Mine and Ours (1968), opposite Lucille Ball and Henry Fonda, and «genre pictures» in Europe, including the Spaghetti Western The Price of Power (1969), in which he played President James Garfield.

Operations for skin cancer and the removal of a lymph gland removed Van from public life in the mid 1960s, but he was back on television and in feature films by the end of the decade. Now established as an affable supporting star, he appeared in family comedies like Yours, Mine and Ours (1968), opposite Lucille Ball and Henry Fonda, and «genre pictures» in Europe, including the Spaghetti Western The Price of Power (1969), in which he played President James Garfield.

Throughout the 1980s, he was busy in summer stock and dinner theater. In 1985, he received critical and box-office acclaim when he returned to Broadway to replace original star Gene Barry in the musical La Cage aux Folles. Based on the eponymous French play by Jean Poiret, and with music and lyrics by Jerry Herman and a book by Harvey Fierstein, it tells the story of a gay couple, Georges, the manager of a Saint-Tropez nightclub featuring drag entertainment, and Albin, his romantic partner and star attraction, and the farcical adventures that ensue when Georges's son brings home his fiancé's ultra-conservative parents to meet them. The production was a massive success, winning six Tony Awards, including Best Musical.

|

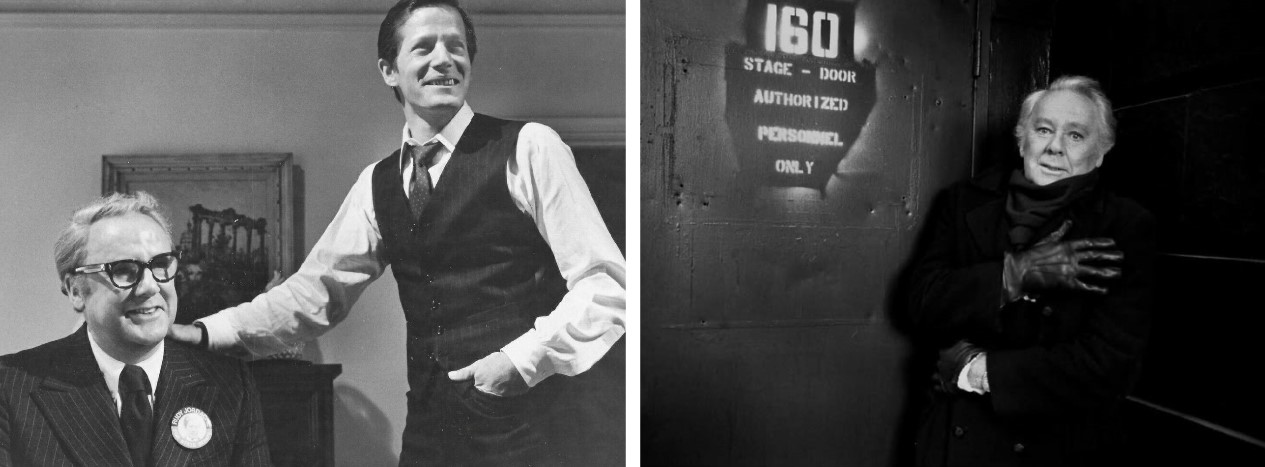

| LEFT: Van Johnson and Peter Strauss in Rich Man, Poor Man. RIGHT: Van Johnson at stage door during his appearance on Broadway in La Cage aux Folles. |

After retiring to an assisted living facility in the new millennium, Johnson died on December 12, 2008, at the age of 92. His legacy was a true rarity in movie circles — he had outlasted virtually all male actors from the Golden Age of Hollywood and had managed to work solidly way into his golden years, unlike many of his peers. In Hollywood folklore, he will live on as the ultimate boy-next-door. For me, he will always be Charles, the boy with the golden hair and the silly smile.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's «Golden Boy,» also known as Van Johnson, was born Charles Van Dell Johnson on August 25, 1916 in Newport, Rhode Island. He was the only child of Loretta (neé Snyder), a housewife from a Pennsylvania Dutch background, and Charles E. Johnson, a plumber and later real-estate salesman of Swedish descent. From the beginning, the free-spirited Loretta felt miserable in her marriage to Charles, a tough-minded, pragmatic man who valued thrift over material comfort. The arrival of a son merely added more pressure to the young couple's dismal relationship, and ultimately drove Loretta to alcoholism.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's «Golden Boy,» also known as Van Johnson, was born Charles Van Dell Johnson on August 25, 1916 in Newport, Rhode Island. He was the only child of Loretta (neé Snyder), a housewife from a Pennsylvania Dutch background, and Charles E. Johnson, a plumber and later real-estate salesman of Swedish descent. From the beginning, the free-spirited Loretta felt miserable in her marriage to Charles, a tough-minded, pragmatic man who valued thrift over material comfort. The arrival of a son merely added more pressure to the young couple's dismal relationship, and ultimately drove Loretta to alcoholism.

Comments

Post a Comment