Audrey Hepburn and the Dutch Resistance

Born in Brussels, Belgium, Audrey Hepburn moved to Kent, England with her mother, Baroness Ella van Heemstra, after her parents' separation in the late 1930s. When Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, Ella relocated with her ten-year-old daughter to her native Netherlands, setting up residence in the van Heemstra ancestral family home in Arnhem, located about 50 miles (80 kilometres) southeast of Amsterdam. She believed the country would remain neutral and be spared of a German attack, as it had happened during World War I. For the next five years, Audrey attended the Arnhem Conservatory of Music and Dance, where she developed an interest in theatre and trained in ballet.

|

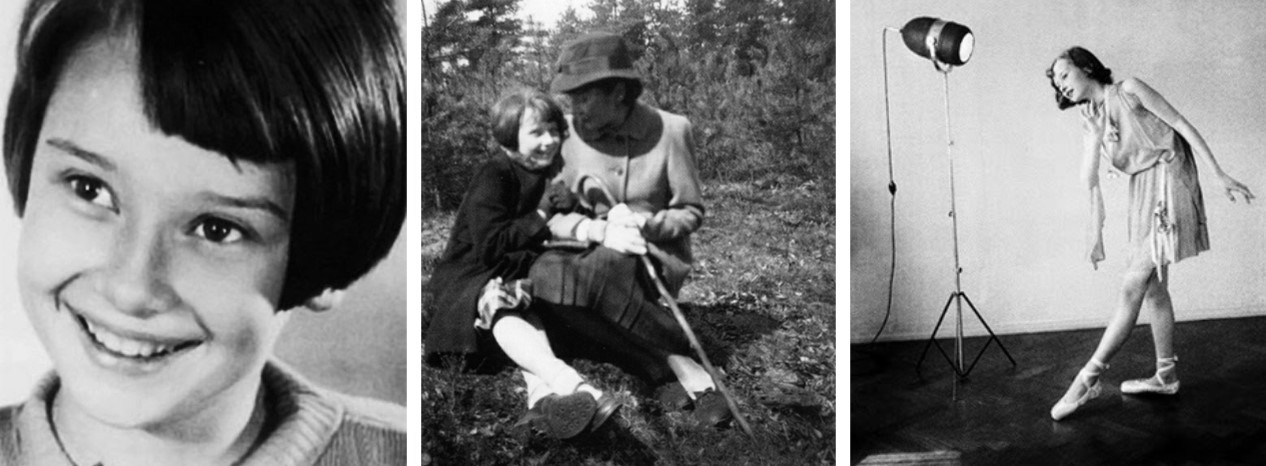

| LEFT: Audrey Hepburn in 1939. MIDDLE: Audrey Hepburn with her mother in Arnhem. RIGHT: One of her first professional photoshoots (April 1942). |

As tensions grew in Europe, Ella became deeply involved in helping create a Dutch resistance movement in the likely scenario of a German takeover of the Netherlands. The movement revolved around activities in Arnhem, where Ella hosted informal gatherings in an attempt to bring in more volunteers to the resistance. Five days after Germany occupied the Netherlands, in a surprise attack in May 1940, Ella and the Dutch resistance joined forces to blow up trains, bridges and ammunition dumps in an effort to hinder the invaders.

Some members of the Dutch resistance were caught and subsequently executed. One of them was Ella's brother, Willem, an attorney who was killed by firing squad in the town square with five other men after bravely destroying a train filled with German soldiers. Ella's nephew, Frans, was also executed by the Germans for his resistance activities. Fearing for her daughter's safety because of her English-sounding name and background, as well as the fact that she spoke that language, Ella changed Audrey's name to Edda van Heemstra and instructed her to speak Dutch. She maintained her new identity for the duration of the war.

Some members of the Dutch resistance were caught and subsequently executed. One of them was Ella's brother, Willem, an attorney who was killed by firing squad in the town square with five other men after bravely destroying a train filled with German soldiers. Ella's nephew, Frans, was also executed by the Germans for his resistance activities. Fearing for her daughter's safety because of her English-sounding name and background, as well as the fact that she spoke that language, Ella changed Audrey's name to Edda van Heemstra and instructed her to speak Dutch. She maintained her new identity for the duration of the war.

|

| LEFT: German paratroopers dropping into The Hague (May 10, 1940). RIGHT: The centre of Rotterdam destroyed after a German air raid (May 14, 1940). |

After the Netherlands was incorporated into Adolf Hitler's Third Reich, the van Heemstras — just like every other aristocratic family in each country in Nazi Germany's «growing sphere» — were devastated financially. Although they were allowed to remain in their home, the Germans confiscated all of their gold and personal jewellery and liquidated their banks accounts.

Audrey found solace in music and ballet, which not only continued to motivate her, but which she also used to aid the resistance in whatever way she could. Some of the money she earned teaching dancing and piano to younger girls at the conservatory was given to the underground, for which she worked constantly, despite the grave danger. Her hatred for the Nazis and everything they represented gave her enough reason to take the risk.

Audrey found solace in music and ballet, which not only continued to motivate her, but which she also used to aid the resistance in whatever way she could. Some of the money she earned teaching dancing and piano to younger girls at the conservatory was given to the underground, for which she worked constantly, despite the grave danger. Her hatred for the Nazis and everything they represented gave her enough reason to take the risk.

It did not take long for Dutch adolescents to take the example of their elders and throw themselves into the battle against the occupying power. Two of these «youthful patriots» were Audrey's older half-brothers, Alexander (1920-1979) and Ian (1924-2010), born of Ella's first marriage to the Dutch aristocrat Hendrik Gustaaf Adolf Quarles van Ufford. They defied the German invaders by refusing to join the Netherlands Institute of Folkish Education, a Nazification youth group located near Arnhem in which boys fitting the Aryan ideal underwent arduous physical training before being recruited by the Nazi movement.

When Alexander went missing in 1941, his family assumed him dead, but in reality he had been fighting with the Dutch troops and was captured after they surrendered. He managed to escape and hid for the remainder of the war. As for Ian, he was dedicated to serving the resistance, handing out fliers, working for an underground radio station, helping organize student riots and encouraging railroad workers to go on strike. Ian's disobedience eventually had him deported to a forced labor camp in Berlin, where he remained for the rest of war.

When Alexander went missing in 1941, his family assumed him dead, but in reality he had been fighting with the Dutch troops and was captured after they surrendered. He managed to escape and hid for the remainder of the war. As for Ian, he was dedicated to serving the resistance, handing out fliers, working for an underground radio station, helping organize student riots and encouraging railroad workers to go on strike. Ian's disobedience eventually had him deported to a forced labor camp in Berlin, where he remained for the rest of war.

The terror that had spread throughout Europe after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 was soon felt in Arnhem. That same month, about 700 young Jewish Dutch men were sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany, where they were eventually murdered.

Non-Jews did not escape the Nazi brutality either. One day in May 1942, 70 Dutch citizens were executed as a reprisal for alleged crimes against the German occupiers, while hundreds of others were mercilessly slaughtered for providing help to British pilots who had been shot down over the Netherlands. Audrey later recalled,

Non-Jews did not escape the Nazi brutality either. One day in May 1942, 70 Dutch citizens were executed as a reprisal for alleged crimes against the German occupiers, while hundreds of others were mercilessly slaughtered for providing help to British pilots who had been shot down over the Netherlands. Audrey later recalled,

«We saw young men put against the wall and shot, and they'd close the street and then open it and you could pass by again [...] Don't discount anything awful you hear or read about the Nazis. It's worse than you could ever imagine.»

Audrey's maternal uncle, Otto van Limburg Stirum, husband of her mother's older sister, Miesje, was also executed in 1942 in retaliation for an act of sabotage by the resistance movement. (Otto was not actually involved in the incident; he was targeted because of his family's longstanding prominence in Dutch society.)

Audrey pretended to be oblivious to the tragedies and dangers surrounding her as she continued to play a role in the resistance. Reportedly, she forged signatures of identity cards and carried coded messages in the heel of her shoe to members of the Dutch underground. At the same time, the lack of food had reached unprecedented proportions in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands. Audrey subsisted on lettuce, bread made with peas and an occasional potato. When the potatoes ran out, she would eat tulip bulbs, which she sometimes used to make flour to bake cakes and biscuits. Since she had gone so long without proper nourishment, Audrey began suffering from malnutrition and lost a considerable amount of weight.

Despite her ailments, Audrey continued to combine her love of dance with her work for the resistance. She and other dancers would put on recitals at the homes of underground workers, including the van Heemstra residence on several occasions. They would lock the doors and windows, draw the blinds, dim the lights and then perform routines that Audrey had choreographed herself, as a friend played the piano. Because of the fear of retribution, no one would clap when the show ended. Instead, they would pass a hat, into which those who could afford it would place money to support the resistance movement. Audrey would later say, «The best audience I ever had made not a single sound at the end of my performances.»

Shortly after D-Day, British general Bernard Montgomery devised a plan called «Operation Market Garden,» in which Allied airborne and ground troops would capture eight Dutch bridges, thereby opening a pathway into Germany. A group of 3,200 paratroopers were to be dropped behind enemy lines in three Dutch towns, the most important of which was Arnhem.

The Battle of Arnhem began on September 17, 1944. The initial surrender of some German troops prompted celebration in the streets by townspeople, who showered the Allied soldiers with flowers. On the second day of Operation Market Garden, however, many airborne troops were shot down by German artillery and street fighting ensued throughout Arnhem, including on the van Heemstra property in nearby Oosterbeek. German tanks destroyed much of Arnhem, as thousands of Allied soldiers were either killed or captured. In the end, the operation that was supposed to have liberated Arnhem from the Nazis turned out to be a terrible failure.

The Battle of Arnhem began on September 17, 1944. The initial surrender of some German troops prompted celebration in the streets by townspeople, who showered the Allied soldiers with flowers. On the second day of Operation Market Garden, however, many airborne troops were shot down by German artillery and street fighting ensued throughout Arnhem, including on the van Heemstra property in nearby Oosterbeek. German tanks destroyed much of Arnhem, as thousands of Allied soldiers were either killed or captured. In the end, the operation that was supposed to have liberated Arnhem from the Nazis turned out to be a terrible failure.

The van Heemstras were among the 90,000 Arnhem citizens who were ordered to evacuate. Ella, Miesje and Audrey moved in with her grandfather, Baron Aarnoud van Heemstra, in neighbouring Velp, where they struggled to survive in a house without food, light and heat. Once again, they were forced to eat tulip bulbs to stay alive. Audrey's legs began to swell with edema and she suffered with jaundice, in addition to acute anemia and respiratory problems.

In April 1945, British and Canadian troops finally liberated Arnhem and other eastern and northern Dutch provinces. On May 5, one day after her 16th birthday, Audrey heard people singing outside the house, as the smell of English cigarettes wafted towards her. The family went upstairs, slowly opened the front door and saw British troops surrounding the house. The German commander-in-chief in the Netherlands had surrendered to the Canadian Army and all major combat operations in the country had come to an end. Three days later, Germany unconditionally surrendered to the Allies, bringing the war in Europe to a close.

In April 1945, British and Canadian troops finally liberated Arnhem and other eastern and northern Dutch provinces. On May 5, one day after her 16th birthday, Audrey heard people singing outside the house, as the smell of English cigarettes wafted towards her. The family went upstairs, slowly opened the front door and saw British troops surrounding the house. The German commander-in-chief in the Netherlands had surrendered to the Canadian Army and all major combat operations in the country had come to an end. Three days later, Germany unconditionally surrendered to the Allies, bringing the war in Europe to a close.

Audrey asked the British soldiers for chocolate and was handed five bars of it. She devoured them all at once, which made her violently ill. Soon, she and millions of others were fed far more nutritionally through the efforts of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), later transformed into the United Nations Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF). The UNRRA placed food, clothing and basic medical supplies in local schools, where Audrey picked out sweaters and skirts that had been shipped from the United States. Three weeks later, Alexander returned home to Arnhem with a pregnant wife, who gave birth to Audrey's nephew that July. Shortly thereafter, Ian also appeared at the front door, having walked most of 325 miles (523 kilometres) from Berlin to Arnhem.

|

| LEFT: Polish labourers, liberated from Nazi camps, at

Weimar Station receiving food and blankets supplied by the UNRRA. RIGHT: Audrey Hepburn in 1946. |

The hunger and terror Audrey Hepburn experienced during World War II sparked her interest and devotion to humanitarian causes later in her life. As a Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF, she dedicated her final years to helping impoverished children in some of the most profoundly disadvantaged communities in Africa, South America and Asia. She visited several orphanages and participated in food, water and immunisation campaigns. In recognition of her extraordinary humanitarian work, she was awarded with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1992. After her untimely death in 1993, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences presented her with the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award, which her son Sean accepted on her behalf.

_____________________________________

SOURCES:

Audrey Hepburn: A Biography by Martin Gitlin (Greenwood Press, 2009)

Enchantment: Life of Audrey Hepburn by Donald Spoto (Harmony Books, 2007)

Comments

Post a Comment