Film Friday: Johnny Belinda (1948)

In honour of Jane Wyman's 100th birthday, which was yesterday, this week on «Film Friday» — the first of 2017 — I thought I would bring you the film that gave her the Academy Award for Best Actress, the only Oscar of her career. I saw this film for the first time yesterday and already it has become one of my all-time favorites.

Directed by Jean Negulesco, Johnny Belinda (1948) tells the story of Belinda McDonald (Jane Wyman), a deaf-mute young woman who leads a sad, lonely existence in a fishing and farming community on a small island in Nova Scotia. She lives with her father, Black (Charles Bickford), and her aunt, Aggie (Agnes Moorehead), who call her «Dummy» and resent her because her mother died giving birth to her. Belinda is befriended by the new local physician, Dr. Robert Richardson (Lew Ayres), who recognizes her intelligence and teaches her sign language. When Black learns that he can communicate with his daughter, a bond develops between them.

Directed by Jean Negulesco, Johnny Belinda (1948) tells the story of Belinda McDonald (Jane Wyman), a deaf-mute young woman who leads a sad, lonely existence in a fishing and farming community on a small island in Nova Scotia. She lives with her father, Black (Charles Bickford), and her aunt, Aggie (Agnes Moorehead), who call her «Dummy» and resent her because her mother died giving birth to her. Belinda is befriended by the new local physician, Dr. Robert Richardson (Lew Ayres), who recognizes her intelligence and teaches her sign language. When Black learns that he can communicate with his daughter, a bond develops between them.

|

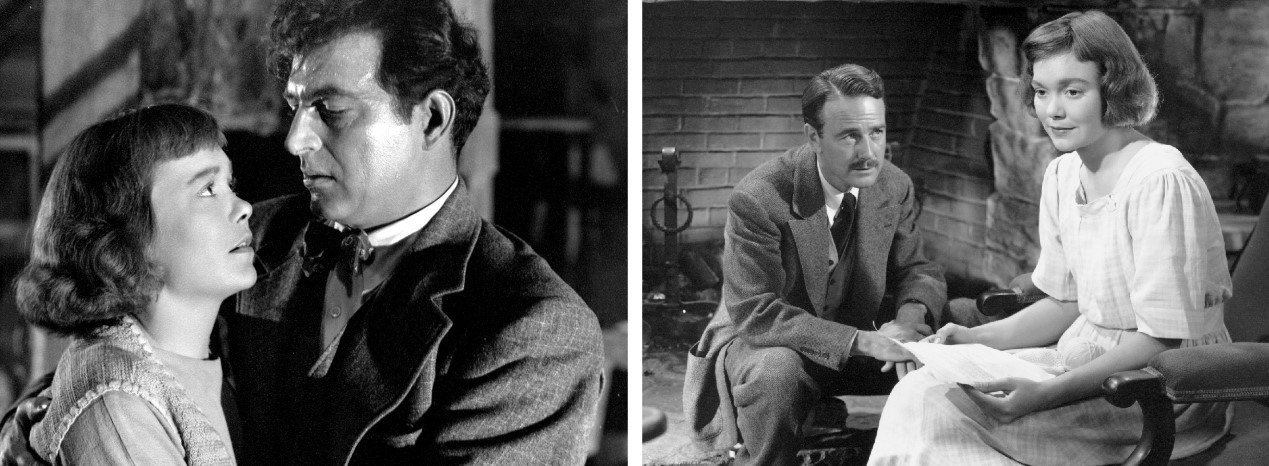

| LEFT: Agnes Moorehead, Jane Wyman, Lew Ayres and Charles Bickford. MIDDLE: Lew Ayres and Jane Wyman. RIGHT: Stephen McNally and Jane Wyman. |

One evening, a group of young people, including bully Lochy McCormick (Stephen McNally) and his girlfriend Stella Maguire (Jan Sterling), Robert's assistant, come by the McDonald farm to collect some flour. An impromptu dance breaks out and Belinda's tentative attempts to dance briefly attract Lochy's attention. Later, having been rejected by Stella, who is secretly in love with Robert, a drunken Lochy goes to the McDonald farm and rapes Belinda, which results in pregnancy. After the birth of the baby, whom Belinda names Johnny, the townspeople begin to shun both the McDonald family and Robert, as they suspect he is father of the child.

When Lochy appears during a storm, Black suddenly realizes that he is Johnny's father and assaults him. In the ensuing fight, Lochy pushes Black off a cliff into the sea, killing him. Certain that Belinda is incapable of caring for her child, the townspeople decide to take the baby from her and give him to Stella and Lochy, who are now married. However, Stella changes her mind when she sees how much Belinda loves Johnny. Lochy then tells Stella that he is determined to take the child because he is the baby's father. When he comes to take the baby away, Belinda shoots and kills him. At Belinda's murder trial, Stella initially refuses to disclose the reason why Locky was killed, but finally tells the truth, and Belinda is acquitted.

When Lochy appears during a storm, Black suddenly realizes that he is Johnny's father and assaults him. In the ensuing fight, Lochy pushes Black off a cliff into the sea, killing him. Certain that Belinda is incapable of caring for her child, the townspeople decide to take the baby from her and give him to Stella and Lochy, who are now married. However, Stella changes her mind when she sees how much Belinda loves Johnny. Lochy then tells Stella that he is determined to take the child because he is the baby's father. When he comes to take the baby away, Belinda shoots and kills him. At Belinda's murder trial, Stella initially refuses to disclose the reason why Locky was killed, but finally tells the truth, and Belinda is acquitted.

Your Lordship, I insist this girl obeyed an impulse older than the laws of man: the instinct of a mother to protect her child. (Dr. Robert Richardson)

In 1908, writer Elmer Blaney Harris had a summer home built for himself and his wife in the small town of Fortune Bridge on Prince Edward Island, a province of Canada. While there, he became acquainted with a deaf-mute millhand named Lydia Dingwell, whose rape by a fisherman and subsequent pregnancy inspired Harris to pen Johnny Belinda in the early 1930s. Although he had originally written it as a play, he first tried to interest Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in his drama, thinking it might work better as a film. The studio toyed with the possibility, but questioned the commercial value of a picture with a non-speaking heroine and worried about the Production Code's mandate that «rape should never be more than suggested.» When MGM decided to pass on the project, Harris took Johnny Belinda to Broadway.

Produced and directed by Harry Wagstaff Gribble, Johnny Belinda opened at the Belasco Theatre in New York City on September 18, 1940. The cast included Helen Craig as Belinda McDonald, the hearing and speech-impaired main character, Louis Hector as her introverted father Black, Clare Woodbury as her spinster aunt Maggie, Willard Parker as Lochy McCormick, the lothario who rapes her, and Stephen McNally as Dr. Jack Davidson, the physician who teaches her lip-reading and sign language. Most critics found Johnny Belinda overwrought and even offensive. For instance, John Mason Brown of The New York Post deemed it «barely passable,» while Richard Watts Jr. of the Herald Tribune called it «just trash.» Nevertheless, the play found a loyal public, running for a total of 321 performances until it closed at the Longacre Theatre on June 21, 1941. The popular success of Johnny Belinda caught the attention of producer Jerry Wald, who convinced Warner Bros. to purchase the screen rights for $50,000, arguing that Paramount and RKO had both made films about hearing and speech-impaired women. In Paramount's And Now Tomorrow (1944), Loretta Young awakens one morning to discover that she cannot hear the rain beating against the window. In RKO's The Spiral Staircase (1946), a traumatic experience renders Dorothy McGuire incapable of speaking until the last scene.

To write the screenplay for Johnny Belinda, Wald hired Allen Vincent and Irma von Cube, who made some changes to the original material. For instance, in Harris's play, Black promises to leave Lochy alone when Dr. Jack says he will marry Belinda and give her child a home. Shortly afterwards, Black is killed by lightning while fixing the fence between his farm and Lochy's property. In the film version, however, the two men get involved in a fight on the edge of a cliff, which culminates with Black falling melodramatically to his death.

The Films of Agnes Moorehead by Axel Nissen (Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2013)

Produced and directed by Harry Wagstaff Gribble, Johnny Belinda opened at the Belasco Theatre in New York City on September 18, 1940. The cast included Helen Craig as Belinda McDonald, the hearing and speech-impaired main character, Louis Hector as her introverted father Black, Clare Woodbury as her spinster aunt Maggie, Willard Parker as Lochy McCormick, the lothario who rapes her, and Stephen McNally as Dr. Jack Davidson, the physician who teaches her lip-reading and sign language. Most critics found Johnny Belinda overwrought and even offensive. For instance, John Mason Brown of The New York Post deemed it «barely passable,» while Richard Watts Jr. of the Herald Tribune called it «just trash.» Nevertheless, the play found a loyal public, running for a total of 321 performances until it closed at the Longacre Theatre on June 21, 1941.

To write the screenplay for Johnny Belinda, Wald hired Allen Vincent and Irma von Cube, who made some changes to the original material. For instance, in Harris's play, Black promises to leave Lochy alone when Dr. Jack says he will marry Belinda and give her child a home. Shortly afterwards, Black is killed by lightning while fixing the fence between his farm and Lochy's property. In the film version, however, the two men get involved in a fight on the edge of a cliff, which culminates with Black falling melodramatically to his death.

Wald initially wanted Johnny Belinda to be directed by Delmer Daves, but he eventually assigned the project to Jean Negulesco. Born in Romania, Negulesco began his career as painter in Bucharest, before moving to the United States in 1927. He entered the film industry in 1932, when he was hired by Paramount Pictures as a sketch artist and technical advisor, notably designing the rape scene in The Story of Temple Drake (1933) without violating the Hays Code. He worked in various capacities during the remainder of the decade, until he was signed by Warner Bros. in 1940 to direct a series of short subjects. Negulesco made his feature film directorial debut with Singapore Woman (1941) and went on to helm a string of noir dramas, including The Conspirators (1944) and Humoresque (1946), the latter produced by Wald.

Eleanor Parker and Teresa Wright were briefly considered for the lead role of Belinda McDonald, but Wald ultimately hired Jane Wyman on the strength of her Oscar nominated performance in The Yearling (1946), made on loan-out to MGM. By the time Wyman was cast in Johnny Belinda, her personal life was in turmoil. Married to fellow Warner Bros. contractee Ronald Reagan since 1940, she had recently given birth to their third child, a girl born four months premature, who died that same day. She and Reagan were also having marital issues, in part caused by his involvement with the Screen Actors Guild, of which he was president. Wanting to set aside her problems, Wyman welcomed the challenge of playing a deaf-mute woman.

Eleanor Parker and Teresa Wright were briefly considered for the lead role of Belinda McDonald, but Wald ultimately hired Jane Wyman on the strength of her Oscar nominated performance in The Yearling (1946), made on loan-out to MGM. By the time Wyman was cast in Johnny Belinda, her personal life was in turmoil. Married to fellow Warner Bros. contractee Ronald Reagan since 1940, she had recently given birth to their third child, a girl born four months premature, who died that same day. She and Reagan were also having marital issues, in part caused by his involvement with the Screen Actors Guild, of which he was president. Wanting to set aside her problems, Wyman welcomed the challenge of playing a deaf-mute woman.

To play the young doctor, whose name was changed from Jack Davidson to Robert Richardson, Wald wanted English-born actors Robert Donat or Ronald Colman, while Negulesco preferred Brian Aherne. Eventually, the role was given to Lew Ayres, who had become a star after his heartfelt performance in All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). This same film made him a confirmed pacifist and later a conscientious objector to World War II. The news that a Hollywood actor was opposed to the war was a major source of public debate, leading MGM to drop Ayres's contract. His reputation was almost destroyed until it was revealed that he had served honorably as a non-combatant medic from 1942 to 1946. Although Warner Bros. had some reservations about casting Ayres, Wald decided he would make the perfect rural physician, remembering how persuasive the actor had been as Dr. Kildare in the eponymous MGM series.

The part of Black McDonald, Belinda's father, was assigned to Charles Bickford, whose versatility as a character actor had earned him Academy Award nominations for The Song of Bernadette (1943) and The Farmer's Daughter (1947). Negulesco initially wanted Anne Revere or Judith Anderson to play Belinda's aunt Aggie, but ultimately cast Agnes Moorehead, another two-time Oscar nominee — for The Magnificent Andersons (1942) and Mrs. Parkington (1944). Janis Paige was considered for the role of Stella Maguire, but the role was offered instead to newcomer Jan Sterling, in her second film appearance. Although Rory Calhoun was at one point slated to play predatory bully Lochy McCormick, the part was given to Stephen McNally, who had played Dr. Jack in the original stage production under the name of Horace McNally.

Studio head Jack Warner was outraged when he saw the daily rushes of Johnny Belinda, complaining that Negulesco was spending too much time showing scenery. He was also horrified that Wyman, one of the studio's biggest female stars, was devoid of glamour and ordered Negulesco to have her wear makeup. In addition, Warner wanted narration added to her close-ups «to tell the public what she was thinking.» When Negulesco ignored all of his suggestions, Warner threatened to fire him, but Wald came to the director's defense, saying: «If Negulesco leaves the picture, I leave the studio.» Warner was so displeased with the film that he let it sit on the shelf for nearly a year before releasing it.

Johnny Belinda had its world premiere in Hollywood on October 14, 1948, nine days before being released to the general public. Critical reviews were generally positive. The notoriously stuffy Bosley Crowther of The New York Times compared the film favorably to the original stage production, calling it «quite moving,» while Variety described it as «tastefully handled.» The cast was uniformly praised, with Jane Wyman receiving the best notices. Crowther deemed her performance «sensitive and poignant» and Variety called it «a personal success.» Grossing $4,100,000 at the box-office, Johnny Belinda was the fifth biggest moneymaker of the year. When the 21st Academy Awards were announced, Johnny Belinda was nominated in twelve categories: Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Lew Ayres), Best Actress (Jane Wyman), Best Supporting Actor (Charles Bickford), Best Supporting Actress (Agnes Moorehead), Best Screenplay, Best Cinematography (Black and White), Best Art/Set Direction (Black-and-White), Best Sound Recording, Best Score and Best Editing.

On March 14, 1949, the awards ceremony took place at the Academy Theatre in Hollywood, where Ronald Colman announced that Jane Wyman was the winner for Best Actress. She was so surprised by her win that she dropped her purse and the contents spilled out on to the floor. She then rushed to the stage and delivered the evening's shortest acceptance speech:

The part of Black McDonald, Belinda's father, was assigned to Charles Bickford, whose versatility as a character actor had earned him Academy Award nominations for The Song of Bernadette (1943) and The Farmer's Daughter (1947). Negulesco initially wanted Anne Revere or Judith Anderson to play Belinda's aunt Aggie, but ultimately cast Agnes Moorehead, another two-time Oscar nominee — for The Magnificent Andersons (1942) and Mrs. Parkington (1944). Janis Paige was considered for the role of Stella Maguire, but the role was offered instead to newcomer Jan Sterling, in her second film appearance. Although Rory Calhoun was at one point slated to play predatory bully Lochy McCormick, the part was given to Stephen McNally, who had played Dr. Jack in the original stage production under the name of Horace McNally.

Johnny Belinda was filmed between September and November 1947. Location shooting took place at Fort Bragg, a town on the coast of northern California, and Mendocino, a lumber village north of San Francisco.

Before production began, Wyman prepared for her role by studying for six months at the Mary E. Bennett School for the Deaf in Los Angeles, where she learned the proper facial and manual requisites of a deaf-mute person. She also spent hours screening 16-mm movies of a deaf girl so that she could become fluent in sign language. Normally right-handed, Wyman used her left hand throughout the film to capture Belinda's uncertainty of motion. She also devised a special way of walking, starting not with the right, but with the left foot. As soon as filming started, Negulesco and Wald noticed that Wyman's facial expressions suggested that she could hear what was being said. To fix this problem, she was fitted with plastic ears and cotton earplugs.

Before production began, Wyman prepared for her role by studying for six months at the Mary E. Bennett School for the Deaf in Los Angeles, where she learned the proper facial and manual requisites of a deaf-mute person. She also spent hours screening 16-mm movies of a deaf girl so that she could become fluent in sign language. Normally right-handed, Wyman used her left hand throughout the film to capture Belinda's uncertainty of motion. She also devised a special way of walking, starting not with the right, but with the left foot. As soon as filming started, Negulesco and Wald noticed that Wyman's facial expressions suggested that she could hear what was being said. To fix this problem, she was fitted with plastic ears and cotton earplugs.

|

| Jane Wyman, Charles Bickford, Lew Ayres and Agnes Moorehead during filming. |

Studio head Jack Warner was outraged when he saw the daily rushes of Johnny Belinda, complaining that Negulesco was spending too much time showing scenery. He was also horrified that Wyman, one of the studio's biggest female stars, was devoid of glamour and ordered Negulesco to have her wear makeup. In addition, Warner wanted narration added to her close-ups «to tell the public what she was thinking.» When Negulesco ignored all of his suggestions, Warner threatened to fire him, but Wald came to the director's defense, saying: «If Negulesco leaves the picture, I leave the studio.» Warner was so displeased with the film that he let it sit on the shelf for nearly a year before releasing it.

Johnny Belinda had its world premiere in Hollywood on October 14, 1948, nine days before being released to the general public. Critical reviews were generally positive. The notoriously stuffy Bosley Crowther of The New York Times compared the film favorably to the original stage production, calling it «quite moving,» while Variety described it as «tastefully handled.» The cast was uniformly praised, with Jane Wyman receiving the best notices. Crowther deemed her performance «sensitive and poignant» and Variety called it «a personal success.» Grossing $4,100,000 at the box-office, Johnny Belinda was the fifth biggest moneymaker of the year.

On March 14, 1949, the awards ceremony took place at the Academy Theatre in Hollywood, where Ronald Colman announced that Jane Wyman was the winner for Best Actress. She was so surprised by her win that she dropped her purse and the contents spilled out on to the floor. She then rushed to the stage and delivered the evening's shortest acceptance speech:

«I accept this very gratefully for keeping my mouth shut for once. I think I'll do it again.»

Hers was the only Oscar that Johnny Belinda received that night. Jean Negulesco lost to John Huston for The Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948), which also gave Walter Huston the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. In turn, Agnes Moorehead lost to Claire Trevor for Key Largo (1948), while Lew Ayres lost to Laurence Olivier for Hamlet (1948), which was named Best Picture that year.

______________________________________________

SOURCES: The Films of Agnes Moorehead by Axel Nissen (Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2013)

The Oxford Companion to American Theatre by Gerald Bordman and Thomas S. Hischak (Oxford University Press, 2004)

The President's Ladies: Jane Wyman and Nancy Davis by Bernard K. Dick (University Press of Mississippi, 2014)

The Women of Warner Brothers: The Lives and Careers of 15 Leading Ladies by Daniel Bubbeo (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002)

In honour of Jane Wyman's 100th birthday, which was yesterday, this week on «Film Friday» — the first of 2017 — I thought I would bring you the film that gave her the Academy Award for Best Actress, the only Oscar of her career. I saw this film for the first time yesterday and already it has become one of my all-time favorites.

In honour of Jane Wyman's 100th birthday, which was yesterday, this week on «Film Friday» — the first of 2017 — I thought I would bring you the film that gave her the Academy Award for Best Actress, the only Oscar of her career. I saw this film for the first time yesterday and already it has become one of my all-time favorites.

Who played the role of the infant, Johnny Belinda, in the 1948 production?

ReplyDelete